Вирус you are owned by

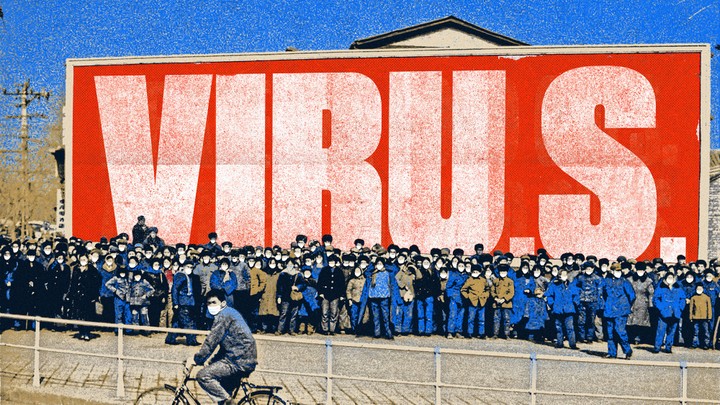

Falsehoods about the virus are spreading widely on the Facebook-owned messaging app.

False information has traveled widely on WhatsApp. | Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

03/16/2020 11:41 PM EDT

The voice of the woman, introducing herself as “Elisabeth … you know, Poldi’s mom,” sounded genuinely concerned.

A friend of hers, who was a doctor at the university hospital of Vienna, had called her with a warning, she said in German. The clinic had noticed that most patients with severe symptoms of COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus pandemic, had taken the painkiller ibuprofen before they were hospitalized. Tests run by the university’s laboratory, she added, had found “strong evidence that ibuprofen accelerates the multiplication of the virus.”

With lightning speed, an audio recording of the message spread among German-language users of WhatsApp, the messenger service owned by Facebook. Quickly, similar recordings referring to alleged research from Vienna in other languages like Slovak also began circulating on the service.

But the WhatsApp message was based on fake information.

“Nonsense,” said Johannes Angerer, a spokesperson for the Medical University of Vienna. “We neither discussed this internally, nor do we conduct any research into the potential effects of ibuprofen on COVID-19.”

While there have been warnings against the use of anti-inflammatory drugs like ibuprofen to treat coronavirus-like symptoms, including by France’s health minister, everything the voice recording said about research efforts at the medical school had been made up, he stressed.

The university released statements to flag the messages as fake within hours after first hearing about them Saturday morning. But the proverbial horse had bolted: German-language Google searches for the keywords “ibuprofen” and “Corona” spiked on Saturday around noon, according to data from the search giant. Over the weekend, the university’s website collapsed temporarily.

The case provides an example of how, as the novel coronavirus spreads across the globe, a wildfire of false and unverified information about the pandemic is following in its wake. On private messaging services like WhatsApp, well-intentioned but fearful individuals are forwarding messages with misleading or doctored information. Other cases range from warnings over made-up extraordinary measures governments might take to keep people in their homes to false numbers of deaths and the level of preparedness of medical services.

“We are aware of an increasing number of false information about the COVID-19 outbreak appearing in public discourse, including on social media,” European Commission Vice President Věra Jourová, whose portfolio includes the EU’s efforts to fight fake news, told POLITICO in an email.

But she also acknowledged that “we need to understand better the risks related to communication on end-to-end encryption services.”

The Vienna fake is far from an isolated case of such digital misinformation — and others often follow a similar pattern that involves people claiming to share insider information with friends and family that they’ve gained access to.

Among Belgian WhatsApp users, an audio message has been circulating with a woman claiming the hospital she worked in had triggered “the maximum pandemic plan.” Other voice recordings warned people of a complete lockdown of the country and urged them to stock up on food.

Poland was hit by a wave of rumors about the government introducing zoning to cities and cutting off transportation to Warsaw. One audio message, recorded by a man who claimed he had a journalist friend with close ties to political decision-makers, said that as of last Sunday, the president would introduce an “emergency state” and that people wouldn’t be able to leave their houses for three weeks.

In France, users forwarded an audio message of a woman who said that she has “a very very very well placed uncle” with ties to national ministers from whom she got information that the whole country would soon be in full quarantine. And in Portugal, a widely circulated voice message suggested that information on the number of infected people in the country was downplayed by official sources, with a man saying: “Forget the numbers the television is talking about. There are thousands of infected in Portugal, confirmed.”

In Ireland, Prime Minister Leo Varadkar pleaded with people on Twitter: “I am urging everyone to please stop sharing unverified info on What’sApp groups. These messages are scaring and confusing people and causing real damage.”

Jourová, who is drafting new proposals on how to protect EU democracies from misinformation, warned that her office was “concerned that some [false claims] can lead to public harm, such as false claims that drinking bleach cures the virus, or abuse the situation for material gain.”

Her office is “is in regular contact with online platforms” to address the issue, she added.

As museums shutter and theaters go dark, cultural institutions have been calling for federal and local government help. Congress’s aid package will provide some assistance.

The so-called coronavirus curve is far from flat, but for many of the country’s arts organizations, revenue certainly is.

Ticket sales are practically nonexistent. Parents are requesting refunds for children’s dance classes. Any live event scheduled for before June is probably canceled, including springtime black-tie galas, which often bring in large chunks of revenue for organizations.

So, like other sectors of the economy, arts organizations have been turning to local and federal taxpayers for help, trying to make the case that American culture needs a bailout, too.

It has not been an easy sell, coming at a time when many pillars of the economy, from airlines to restaurants to public transportation, are facing existential crises and needing handouts themselves. The $2 trillion federal stimulus deal, which was approved by the Senate on Wednesday and awaits a vote in the House, includes $75 million for the National Endowment for the Arts and $75 million for the National Endowment for the Humanities, which can pass on the money to institutions that need it. Another $50 million was designated to the Institute of Museum and Library Services, which distributes funds to museums and libraries.

The figure doesn’t come close to what arts groups pushed for over the last several days. A group representing museums, backed by some Democratic lawmakers in New York and elsewhere, had asked for $4 billion, a dream number few believed would win broad support. Still, the final amount was disappointing to some advocates.

Teresa Eyring, the executive director of Theater Communications Group, a nonprofit that supports regional theaters across the country, said that the money “does not address the severity of the crisis in the not-for-profit arts field.”

One clear victory for the arts sector was a measure that provides federally guaranteed loans to small businesses that pledge not to lay off their workers. That assistance is being made available to nonprofits as well as for-profit companies.

Even in normal times, the federal government gives little support to cultural institutions, apart from the Smithsonian, which was created by Congress. Frequent proposals by Republicans to cut the budget or eliminate the N.E.A., one of the few sources of public revenue for the arts, have put cultural organizations in a permanent defensive stance. And given the current political climate, where some of the arts have become refuges for the anti-Trump resistance, this state of affairs is unlikely to change.

Ellen Walker, the executive director of the Pacific Northwest Ballet in Seattle, said that a common argument against funding the arts sector during periods of financial hardship goes something like this: Arts groups may be “nice,” but they’re far from “necessary.”

At least one Republican lawmaker, Representative Bill Johnson of Ohio, took that stance as Congress debated how to carve up emergency funding for coronavirus relief, questioning why the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, which has had to call off programming because of the pandemic, was being considered for aid.

The stimulus deal includes $25 million for the Kennedy Center, home of the National Symphony Orchestra and Washington National Opera and overseen by a board with representatives and appointees of both parties.

President Trump and First Lady Melania Trump have skipped the last three annual Kennedy Center Honors ceremonies to avoid uncomfortable scenes; some recent honorees have been vocal opponents of Mr. Trump. But at a news conference on Wednesday, President Trump expressed support for the aid, saying he’d “love to see ‘Romeo and Juliet’” at the Kennedy Center but that “you couldn’t go there if you wanted to.”

In an effort to convince skeptics of their importance, cultural institutions have tried to calculate their economic impact in measurable figures that legislators — even those who don’t attend the ballet or the theater regularly — can appreciate. One such statistic: There were 5.1 million jobs associated with arts and culture in 2017, according to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.

In Seattle, a group of about two dozen cultural institutions — including the Pacific Northwest Ballet and the Seattle Opera — added up their attendance in 2019 and compared it with the attendance at home games for the city’s football, baseball and soccer teams. (Their calculations showed about 3.2 million sports fans, compared with 8.7 million arts attendees.) They planned to send the figures to Seattle City Council members to support a potential relief package for arts groups.

The city, which has been hit hard by the virus, is already further along than most when it comes to offering financial help. Seattle has agreed to waive or defer two months of rent payment for arts groups on city-owned property, and the mayor signed a $1.1 million funding package to support cultural organizations.

But art administrators worry that, when divided among a long list of arts groups, the city funding won’t go far.

“That million dollars is going to go very quickly,” said Kevin Malgesini, the managing director of Seattle Children’s Theater. “I don’t anticipate these adding up to enough to save the theater.”

For the children’s theater, which has already had to let go of three full-time positions and cancel the remainder of its seven-play season, resulting in a loss of work for dozens of people, survival will mean designing a patchwork of different funding sources — including city, county and federal assistance, as well as private donations, he said.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, which has projected a shortfall of nearly $100 million this year, started pushing the hashtag #CongressSaveCulture. In a letter to congressional leaders, the American Alliance of Museums warned that museums nationwide are losing at least $33 million each day. The Theater Communications Group urged organizations to contact their members of Congress.

“This isn’t a frivolous, fun little thing,” Representative Chellie Pingree, a Maine Democrat and leader of the Congressional Arts Caucus, said on Monday. “This is an employer of a lot of people and a big sector of the economy.”

Nongovernmental funding streams dedicated to Covid-19 relief have already started up, including a $75 million fund set up by the New York Community Trust, which is offering grants and loans to cultural nonprofits as well as social service agencies.

At a time of enormous uncertainty, arts administrators are looking to measures taken during the 2008 fiscal crisis for some sense of how federal funding will work.

In 2009, as part of a larger economic stimulus, Congress appropriated $50 million to the N.E.A. Similar to what the current stimulus package requires, 60 percent of those funds went directly to grants for nonprofit arts organizations, while the rest went to state and regional arts organizations. The N.E.A. said that the grants helped preserve 7,000 arts jobs.

In Europe, politicians have also recognized cultural workers’ urgent need for support. On Tuesday evening, Arts Council England, which is supported by lottery revenue, announced a £160 million package — some $180 million — to help arts groups and workers in the country.

Support for freelancers, including artists and writers, has been made available in some countries like Germany. In Berlin, they can apply for a 5,000 euro grant, worth about $5,400.

Ginny Louloudes, the executive director of the Alliance of Resident Theaters in New York, said that it’s already difficult asking the government to support the arts when there’s no pandemic. Now, administrators have to tread lightly.

“We have to realize that the city needs to build hospitals, it needs to staff hospitals, it needs masks,” she said. “We have to be very careful about how we frame the message.”

Alex Marshall contributed reporting.

Frequently Asked Questions and Advice

Updated April 11, 2020

This is a difficult question, because a lot depends on how well the virus is contained. A better question might be: “How will we know when to reopen the country?” In an American Enterprise Institute report, Scott Gottlieb, Caitlin Rivers, Mark B. McClellan, Lauren Silvis and Crystal Watson staked out four goal posts for recovery: Hospitals in the state must be able to safely treat all patients requiring hospitalization, without resorting to crisis standards of care; the state needs to be able to at least test everyone who has symptoms; the state is able to conduct monitoring of confirmed cases and contacts; and there must be a sustained reduction in cases for at least 14 days.

The Times Neediest Cases Fund has started a special campaign to help those who have been affected, which accepts donations here. Charity Navigator, which evaluates charities using a numbers-based system, has a running list of nonprofits working in communities affected by the outbreak. You can give blood through the American Red Cross, and World Central Kitchen has stepped in to distribute meals in major cities. More than 30,000 coronavirus-related GoFundMe fund-raisers have started in the past few weeks. (The sheer number of fund-raisers means more of them are likely to fail to meet their goal, though.)

If you’ve been exposed to the coronavirus or think you have, and have a fever or symptoms like a cough or difficulty breathing, call a doctor. They should give you advice on whether you should be tested, how to get tested, and how to seek medical treatment without potentially infecting or exposing others.

The C.D.C. has recommended that all Americans wear cloth masks if they go out in public. This is a shift in federal guidance reflecting new concerns that the coronavirus is being spread by infected people who have no symptoms. Until now, the C.D.C., like the W.H.O., has advised that ordinary people don’t need to wear masks unless they are sick and coughing. Part of the reason was to preserve medical-grade masks for health care workers who desperately need them at a time when they are in continuously short supply. Masks don’t replace hand washing and social distancing.

If you’re sick and you think you’ve been exposed to the new coronavirus, the C.D.C. recommends that you call your healthcare provider and explain your symptoms and fears. They will decide if you need to be tested. Keep in mind that there’s a chance — because of a lack of testing kits or because you’re asymptomatic, for instance — you won’t be able to get tested.

It seems to spread very easily from person to person, especially in homes, hospitals and other confined spaces. The pathogen can be carried on tiny respiratory droplets that fall as they are coughed or sneezed out. It may also be transmitted when we touch a contaminated surface and then touch our face.

No. Clinical trials are underway in the United States, China and Europe. But American officials and pharmaceutical executives have said that a vaccine remains at least 12 to 18 months away.

Unlike the flu, there is no known treatment or vaccine, and little is known about this particular virus so far. It seems to be more lethal than the flu, but the numbers are still uncertain. And it hits the elderly and those with underlying conditions — not just those with respiratory diseases — particularly hard.

If the family member doesn’t need hospitalization and can be cared for at home, you should help him or her with basic needs and monitor the symptoms, while also keeping as much distance as possible, according to guidelines issued by the C.D.C. If there’s space, the sick family member should stay in a separate room and use a separate bathroom. If masks are available, both the sick person and the caregiver should wear them when the caregiver enters the room. Make sure not to share any dishes or other household items and to regularly clean surfaces like counters, doorknobs, toilets and tables. Don’t forget to wash your hands frequently.

Plan two weeks of meals if possible. But people should not hoard food or supplies. Despite the empty shelves, the supply chain remains strong. And remember to wipe the handle of the grocery cart with a disinfecting wipe and wash your hands as soon as you get home.

That’s not a good idea. Even if you’re retired, having a balanced portfolio of stocks and bonds so that your money keeps up with inflation, or even grows, makes sense. But retirees may want to think about having enough cash set aside for a year’s worth of living expenses and big payments needed over the next five years.

Watching your balance go up and down can be scary. You may be wondering if you should decrease your contributions — don’t! If your employer matches any part of your contributions, make sure you’re at least saving as much as you can to get that “free money.”

In a new era of tinfoil-hat diplomacy, official sources are legitimizing conspiracy theories from the internet.

Updated at 9:45 p.m. on April 11, 2020

T he coronavirus that became a global pandemic first surfaced late last year in Wuhan, China. But according to one common narrative making its way around Chinese messaging apps, an American soldier was patient zero. “Chinese netizens and experts” are urging the United States to release health information about a U.S. delegate who attended the Military World Games in Wuhan, asserted a February 22 story from Global Times. The publication, an offshoot of the Chinese Communist Party organ People’s Daily, insinuated that a U.S. military cyclist might have brought the disease from Fort Detrick in Maryland. Chatter about American origins of the disease had begun a month earlier, in the wilds of China’s chat services and on tiny YouTube channels. That alone wouldn’t have amounted to much; conspiracies are as common on social media as ants at a picnic, and the small accounts speculating about “bioweapons” and “the USA virus” got little early traction.

But this time, Chinese state media picked up the story from internet chatter and turned it into an international phenomenon involving not only official media channels but influential diplomats as well. State channels with massive Facebook followings backed away from prior acknowledgments that the virus had originated in Wuhan, recasting the idea as merely a theory—just one of many unknowns. Zhao Lijian, the spokesman and deputy director general of the Information Department of China’s Foreign Ministry, speculated to his half-million followers on Twitter that the United States was secretly concealing early 2020 COVID-19 deaths in annual flu counts. In an unusually overt act of tinfoil-hat diplomacy, he shared an article from the notorious anti-American crackpot site GlobalResearch. The headline reads, “COVID-19: Further Evidence that the Virus Originated in the U.S.”

While spreading conspiracy theories—stories involving claims that shadowy, powerful interests have secretly engineered events to their own advantage—is a time-honored ploy by which states try to discredit their rivals, the first global pandemic of the social-media era shows just how efficiently wild theories can travel. And as Zhao’s Twitter account shows, state-sponsored propaganda has become deeply entangled with anonymous conspiracy mongering. Authority figures are now legitimizing tropes from the recesses of the internet—and ensuring mass popular awareness of those ideas.

State-sponsored media have long played a role in geopolitical power games. Since World War II, the TV, radio, and print media channels of many governments have created what some experts call “white propaganda”: messaging for which official sources claim authorship. (In gray and black propaganda, the origins are partially or entirely concealed.) In the present day, white propaganda has expanded to include the social-network presences of official channels, as well as the individual accounts of bureaucrats and top politicians. Sometimes, the messages these outlets carry are meant for a regime’s own citizens; other times, the outside world.

Messaging from state media also goes by another, friendlier name: public diplomacy. While academics debate the line between propaganda and public diplomacy, in an interconnected world, having the ability to shape narratives is an imperative. The long-term goal is to make people think favorably of the country and its rulers. In other words, it’s a branding exercise. But in the shorter term, state media channels are also used for more direct advocacy campaigns, convincingly conveying an official point of view on specific issues to those outside its borders. In more heated times, this may extend to smearing an adversary’s government, institutions, or policies. But the narrative manipulation around COVID-19 on China’s official state channels has escalated far beyond spin to outright conspiracy.

From the beginning, the Chinese Communist Party has been struggling to manage both domestic and outside perception of its handling of the outbreak of the disease now known as COVID-19. The coronavirus’s rapid spread within China, and its high death toll, triggered a domestic crisis of confidence in President Xi Jinping’s leadership. Although dissent is often quickly censored, Chinese social-media forums were flooded with comments about Xi being “gutless” for not going to Wuhan, among other criticisms. The situation didn’t play any better internationally: The revelation that the Chinese government knew of the outbreak for two full weeks before taking steps to contain it outraged people worldwide and prompted accusations of a cover-up.

As the crisis has begun to recede within China, with Wuhan exiting lockdown and new infections dropping to a trickle, the Communist Party’s public-diplomacy efforts have gone into overdrive: At the Stanford Internet Observatory, where I work, we gathered months of China’s English-language state-media Facebook posts, identifying key themes that were pushed repeatedly: stories of survival rather than deaths, glowing coverage of the “construction miracle” of new hospitals (whose sudden appearance was framed as the result of patriotic engineering ingenuity, rather than as proof of the need to bolster an overwhelmed medical system), and claims that China had bought the world time through its aggressive containment procedures. One remarkable China Daily article from February 20 boasted, “Were it not for the unique institutional advantages of the Chinese system, the world might be battling a devastating pandemic.” The item also slammed international criticism as the result of “ingrained bias against the country.” Other stories presented a rosy revisionist history. State media coverage of the death of the whistleblower optometrist, Li Wenliang, mourned him as a hero, and entirely neglected to mention his detention by police after he discussed the emerging virus in a chat group of close friends. As the writer Louisa Lim put it in Foreign Policy, “China is trying to rewrite the present.”

The Chinese Communist Party has prioritized “persuasion and information management” for years. It has amassed an extensive white-propaganda apparatus since 2000, building and buying TV, radio, and print media, optimizing localized content and messaging in a wide range of languages. Since 2015, it has invested in building a massive English-language presence for its media properties on the very same social networks it has banned within its own border. The English-language Facebook pages for the state-owned newspaper China Daily and the official Xinhua News Agency have more than 75 million followers each; and the China Global Television Network has a following of 99 million; by contrast, CNN has 32 million and Fox News has 18 million. Part of this growth has come from running paid ads on social-media platforms that China’s own citizens are blocked from using. My team has studied hundreds of state-media ads from Facebook’s recently launched political-ads archive. They are targeted at English speakers worldwide. Throughout 2019, the ads frequently involved friendly images of pandas and kittens, highlighted Chinese art and culture, and amplified feel-good political stories.

In February 2020, they took a different turn. The ads began boosting state media coverage of the coronavirus, with dozens of ads praising Xi for his leadership and emphasizing China’s ability to contain the disease. They incorporated hashtags such as #UnityIsStrength and #CombatCoronavirus, predictions of a quick economic recovery, and stories in which world leaders in Italy, Serbia, and elsewhere express gratitude to China. By March 2020, angry ads appeared in the mix, promoting outraged coverage of President Donald Trump’s use of the term Chinese virus.

Of course, Facebook pages for broadcast media aren’t the Communist Party’s only messaging tool. For years, it has also run peer-to-peer persuasion strategies involving influencers, trolls, bots, and commenter armies. The comment legions—called Wumao, or the 50 Cent Army—have been a shadowy presence on China’s internet and message- board ecosystem for more than a decade. The party has also tried using Twitter bots and Facebook sock puppets, including those uncovered during the 2019 Hong Kong protests. ProPublica and other investigative journalism teams have reported that similar shenanigans are happening in the coronavirus conversation as well, though attribution remains a challenge; connecting hypernationalist activity back to direct orders from the party is difficult.*

That managing the narrative is a top priority for the Communist Party is abundantly clear. Among the nine members of China’s task force for managing the COVID-19 response are the party’s policy czar for ideology and propaganda and the director of its Central Propaganda Department.

P olitical conspiracy theories appear even in the analog propaganda of decades past. Mark Fenster, the author of Conspiracy Theories: Secrecy and Power in American Culture, describes them as a “populist theory of power” serving an important communication function: helping unite the audience (“the people”) against an imagined secretive, powerful elite. So when state media in China, for example, create or spread these theories, the elite puppet master is the United States, a geopolitical rival. By exposing the villainy of its adversary, the Chinese Communist Party presents itself as a defender of its people.

The “bioweapon” trope is particularly useful, because it can be readily applied to any disease outbreak. During the Cold War, the KGB’s information-operations department was a notorious practitioner of conspiracy as statecraft. Perhaps its greatest hit was the widely believed claim that a secret U.S. government lab created AIDS. A Soviet telegram explaining the operation may sound familiar to those following COVID-19 news today:

The goal of these measures is to create a favorable opinion for us abroad that this disease is the result of secret experiments with a new type of biological weapon by the secret services of the USA and the Pentagon that spun out of control.

That narrative was initially placed in a pro-Soviet Indian newspaper by way of a whistleblower-style anonymous “letter to the editor” in 1983. It spread through newspapers in 80 countries over a period of four years; the Soviets occasionally revived it with relevant twists for whatever local media environment was of strategic interest. But in the era of Facebook and WeChat, these stories become a high-speed information virus themselves, and the murky source of the initial claim disappears as messages spread across chat groups.

State media outlets rarely transmit conspiracies in the form of bold, direct claims. They usually do it through a combination of insinuations: We’re just asking questions, really. This sometimes happens via interviews with conspiracy-theorist guests who claim they’ve been silenced by their own government, or publishing provocative headlines. Russia has elevated this to an art form, with the English-language RT and Sputnik networks regularly featuring those purportedly censored by the American media.

While easy to mock, tinfoil-hat diplomacy serves a purpose for China. Domestically, it’s allowed the Communist Party to distance itself from its own failings by reframing a poorly managed crisis as something that was inflicted on the Chinese people by outsiders. And Chinese state media are far from the only state source “just asking questions” during this pandemic. RT is hosting American kooks who allege on social media that the virus is part of a mass-vaccination campaign masterminded by Bill Gates, while Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, is referencing claims that the virus was “specifically built for Iran using the genetic data of Iranians.” Americans aren’t above this kind of rumor mongering. Senator Tom Cotton of Arkansas darkly noted the existence of a Wuhan “biosafety level-four super laboratory” in comments on Twitter and to the media, speculating that COVID-19 is a Chinese bioweapon. But neither mainstream American media nor U.S. government-sponsored entities such as Voice of America are pushing conspiracies as a public-diplomacy strategy. U.S. leaders are, however, demanding increased attention to the information war: Senators Mitt Romney, Marco Rubio, and Cory Gardner are calling for a task force to counter Chinese propaganda, and to provide U.S. embassies with guidance on how to counter false narratives locally.

The tension from the information war between the United States and China on the origin of COVID-19 has resulted in increased political brinkmanship; Trump’s administration has requested that the United Nations Security Council include a statement verifying that the virus originated in China in a COVID-19 resolution. Diplomats have been summoned. U.S. reporters have lost press credentials in China. This is not an ideal state of relations at any time, let alone during a pandemic that requires international cooperation.

But letting these narratives spread unchallenged is also not an option. Social-media companies should be paying far closer attention to the stories they’re allowing state-media propagandists to pay to boost. Allowing misleading narratives to take hold during a pandemic can cause immeasurable harm, and risks turning the major tech platforms into accomplices in the deliberate spread of lies. We must keep the focus on finding cures, not fighting over conspiracies.

*An earlier version of this article misattributed a story published by ProPublica.

Читайте также: