Вирус other что это

“It’s not about you, it’s about everybody else.”

Share this story

This story is part of a group of stories called ![]()

Finding the best ways to do good.

If you think you don’t have a huge role to play in how the coronavirus outbreak plays out, think again. You have the potential to make this pandemic so much worse.

That’s because the coronavirus is both more contagious and more deadly than the common flu. One person can easily transmit it to other people without knowing it, and those people would then transmit it to even more people, creating a terrifying snowball effect.

The good news is, just as you can easily transmit the virus to other people, you can easily avoid transmitting it — if you’re willing to stay home. That’s right: Simply by sitting on your couch, you can potentially save lives.

To see why, check out the visualization below. It shows how one person with the coronavirus, who passes on the virus to three other people (some experts say three is the average, though others estimate the infectiousness is a bit lower), can very quickly spawn a public health nightmare that afflicts thousands of people. But it also shows how one person can mitigate that effect through social distancing. By avoiding the office, the barbecue, the airport, and so on, an individual can deprive the virus of the opportunity to infect more people.

One striking real-world example of this phenomenon is the woman known as Patient 31. South Korea had only 30 cases of Covid-19 until, in February, she became infected and started inadvertently spreading the virus. Despite having a fever, she had lunch with a friend at a hotel and attended church services, coming into physical contact with many of the worshippers. In a matter of days, hundreds of people from the church and its environs tested positive for Covid-19.

You do not want to be Patient 31.

This is why even if you’re young and healthy and falsely believe the virus can’t kill you (it can), you’d do well to stay home in order to protect others — especially older and immunocompromised people who are at greater risk of dying if they contract Covid-19, as well as the health care workers who have to expose themselves to the risk every day.

Believe it or not, through the simple act of staying home, you can save many people — even many thousands of people — from contracting the virus.

Hugh Montgomery, director of the Institute for Human Health and Performance at University College London, broke down the math in an incredibly clear and simple video.

This is the best and clearest explanation of why people need to stay at home you could ever wish to see pic.twitter.com/49MgadlctI

To figure out just how infectious a disease is, experts use the basic reproduction number, called the R0 (pronounced “R naught”). That refers to how many other people one sick person will infect on average in a group that doesn’t already have immunity. The higher the R0, the higher the likelihood that many people will get sick.

The R0 for the common flu is 1.3. So, if you get the flu, you will, on average, pass that on to 1.3 people. Montgomery calculates that if each of those 1.3 people pass it on to another 1.3 people, and that keeps on happening 10 times, then by the 10th time, 14 people will have the flu.

(That’s because 1.3 to the power of 10 is 13.786. He’s rounding up a bit.)

The coronavirus, however, is more contagious than the common flu. Experts are still trying to figure out the R0, and in any case it’s not something that’s precisely fixed, since diseases behave differently in different environments and some people (known as “super-spreaders”) are more contagious than others. But the World Health Organization says most estimates of the coronavirus’s R0 are around 2 or 2.5, while some estimates put it as high as 3.11. Montgomery uses an R0 of 3 to make his calculations.

“So every person passes to it three — now that doesn’t sound like much of a difference, but if each of those three pass it to three and that happens in 10 layers, I have been responsible for infecting 59,000 people,” he says.

(That’s because 3 to the power of ten is 59,049. He’s rounding down a bit.)

Montgomery’s back-of-the-envelope math simplifies reality a little; for example, he assumes that all the people in all 10 layers of transmission will be susceptible to contracting the virus, whereas some might already have immunity to it. But his basic point holds up.

And the conclusion he draws at the end is crucial: “If you are irresponsible enough to think that you don’t mind if you get the flu, remember it’s not about you — it’s about everybody else.”

Although it can be genuinely hard to act altruistically when the beneficiaries are so invisible — after all, you won’t be able to see the grandfather or nurse you’ve kept from getting sick — please know that the benefits are real nonetheless.

Every day that you practice social distancing during the pandemic, you’re doing someone else (maybe hundreds or even thousands of someone elses) a great kindness. So if you can, stay home. It’s the easiest act of heroism you’ll ever do.

Sign up for the Future Perfect newsletter and we’ll send you a roundup of ideas and solutions for tackling the world’s biggest challenges — and how to get better at doing good.

Get our newsletter in your inbox twice a week.

Future Perfect is funded in part by individual contributions, grants, and sponsorships. Learn more here.

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection (STI). HPV is a different virus than HIV and HSV (herpes). 79 million Americans, most in their late teens and early 20s, are infected with HPV. There are many different types of HPV. Some types can cause health problems including genital warts and cancers. But there are vaccines that can stop these health problems from happening.

You can get HPV by having vaginal, anal, or oral sex with someone who has the virus. It is most commonly spread during vaginal or anal sex. HPV can be passed even when an infected person has no signs or symptoms.

Anyone who is sexually active can get HPV, even if you have had sex with only one person. You also can develop symptoms years after you have sex with someone who is infected. This makes it hard to know when you first became infected.

In most cases, HPV goes away on its own and does not cause any health problems. But when HPV does not go away, it can cause health problems like genital warts and cancer.

Genital warts usually appear as a small bump or group of bumps in the genital area. They can be small or large, raised or flat, or shaped like a cauliflower. A healthcare provider can usually diagnose warts by looking at the genital area.

HPV can cause cervical and other cancers including cancer of the vulva, vagina, penis, or anus. It can also cause cancer in the back of the throat, including the base of the tongue and tonsils (called oropharyngeal cancer).

Cancer often takes years, even decades, to develop after a person gets HPV. The types of HPV that can cause genital warts are not the same as the types of HPV that can cause cancers.

There is no way to know which people who have HPV will develop cancer or other health problems. People with weak immune systems (including those with HIV/AIDS) may be less able to fight off HPV. They may also be more likely to develop health problems from HPV.

You can do several things to lower your chances of getting HPV.

Get screened for cervical cancer. Routine screening for women aged 21 to 65 years old can prevent cervical cancer.

If you are sexually active

- Use latex condoms the right way every time you have sex. This can lower your chances of getting HPV. But HPV can infect areas not covered by a condom – so condoms may not fully protect against getting HPV;

- Be in a mutually monogamous relationship – or have sex only with someone who only has sex with you.

HPV vaccination is recommended at age 11 or 12 years (or can start at age 9 years) and for everyone through age 26 years, if not vaccinated already.

Vaccination is not recommended for everyone older than age 26 years. However, some adults age 27 through 45 years who are not already vaccinated may decide to get the HPV vaccine after speaking with their healthcare provider about their risk for new HPV infections and the possible benefits of vaccination. HPV vaccination in this age range provides less benefit. Most sexually active adults have already been exposed to HPV, although not necessarily all of the HPV types targeted by vaccination.

At any age, having a new sex partner is a risk factor for getting a new HPV infection. People who are already in a long-term, mutually monogamous relationship are not likely to get a new HPV infection.

There is no test to find out a person’s “HPV status.” Also, there is no approved HPV test to find HPV in the mouth or throat.

There are HPV tests that can be used to screen for cervical cancer. These tests are only recommended for screening in women aged 30 years and older. HPV tests are not recommended to screen men, adolescents, or women under the age of 30 years.

Most people with HPV do not know they are infected and never develop symptoms or health problems from it. Some people find out they have HPV when they get genital warts. Women may find out they have HPV when they get an abnormal Pap test result (during cervical cancer screening). Others may only find out once they’ve developed more serious problems from HPV, such as cancers.

HPV (the virus): About 79 million Americans are currently infected with HPV. About 14 million people become newly infected each year. HPV is so common that almost every person who is sexually-active will get HPV at some time in their life if they don’t get the HPV vaccine.

Health problems related to HPV include genital warts and cervical cancer.

Genital warts: Before HPV vaccines were introduced, roughly 340,000 to 360,000 women and men were affected by genital warts caused by HPV every year.* Also, about one in 100 sexually active adults in the U.S. has genital warts at any given time.

Cervical cancer: Every year, nearly 12,000 women living in the U.S. will be diagnosed with cervical cancer, and more than 4,000 women die from cervical cancer—even with screening and treatment.

There are other conditions and cancers caused by HPV that occur in people living in the United States. Every year, approximately 19,400 women and 12,100 men are affected by cancers caused by HPV.

*These figures only look at the number of people who sought care for genital warts. This could be an underestimate of the actual number of people who get genital warts.

If you are pregnant and have HPV, you can get genital warts or develop abnormal cell changes on your cervix. Abnormal cell changes can be found with routine cervical cancer screening. You should get routine cervical cancer screening even when you are pregnant.

There is no treatment for the virus itself. However, there are treatments for the health problems that HPV can cause:

STD information and referrals to STD Clinics

CDC-INFO

1-800-CDC-INFO (800-232-4636)

TTY: 1-888-232-6348

In English, en Español

Scientists took conspiracy theories about SARS-CoV-2’s origins seriously, and debunked them

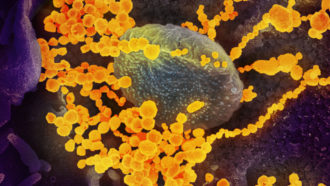

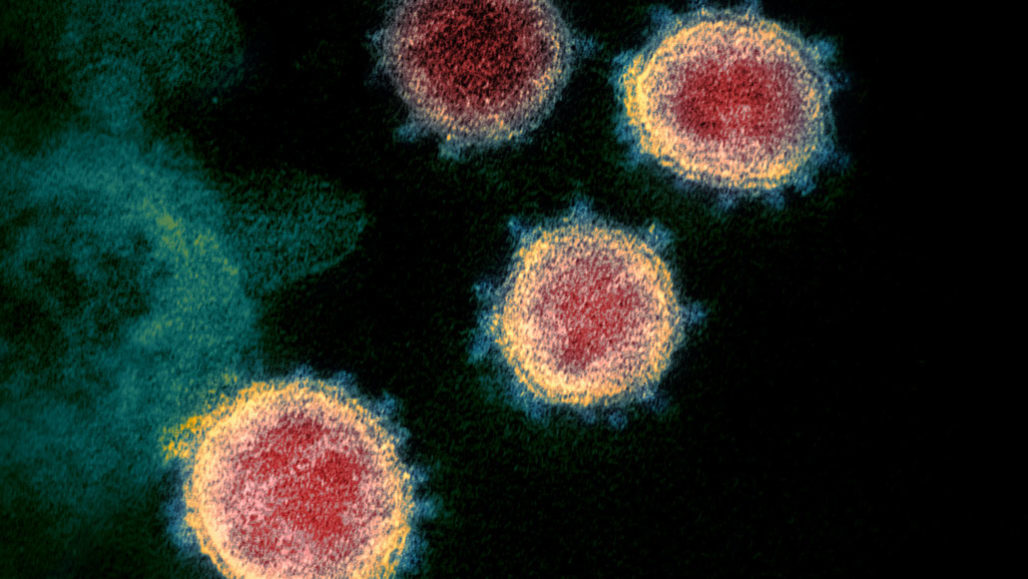

The SARS-CoV-2 virus (seen in this transmission electron microscope image of virus isolated from a U.S. patient), which causes COVID-19, was rumored to be human-made, but scientists have now debunked that theory.

March 26, 2020 at 6:00 am

The coronavirus pandemic circling the globe is caused by a natural virus, not one made in a lab, a new study says.

The virus’s genetic makeup reveals that SARS-CoV-2 isn’t a mishmash of known viruses, as might be expected if it were human-made. And it has unusual features that have only recently been identified in scaly anteaters called pangolins, evidence that the virus came from nature, Kristian Andersen and his colleagues report March 17 in Nature Medicine.

When Andersen, an infectious disease researcher at the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, Calif., first heard about the coronavirus causing an outbreak in China, he wondered where the virus came from. Initially, researchers thought the virus was being spread by repeated infections jumping from animals in a seafood market in Wuhan, China, into humans and then being passed person to person. Analysis from other researchers has since suggested that the virus probably jumped only once from an animal into a person and has been spread human to human since about mid-November (SN: 3/4/20).

But shortly after the virus’s genetic makeup was revealed in early January, rumors began bubbling up that maybe the virus was engineered in a lab and either intentionally or accidentally released.

Headlines and summaries of the latest Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

An unfortunate coincidence fueled conspiracy theorists, says Robert Garry, a virologist at Tulane University in New Orleans. The Wuhan Institute of Virology is “in very close proximity to” the seafood market, and has conducted research on viruses, including coronaviruses, found in bats that have potential to cause disease in people. “That led people to think that, oh, it escaped and went down the sewers, or somebody walked out of their lab and went over to the market or something,” Garry says.

Accidental releases of viruses, including SARS, have happened from other labs in the past. So “this is not something you can just dismiss out of hand,” Andersen says. “That would be foolish.”

Andersen assembled a team of evolutionary biologists and virologists, including Garry, from several countries to analyze the virus for clues that it could have been human-made, or grown in and accidentally released from a lab.

“We said, ‘Let’s take this theory — of which there are multiple different versions — that the virus has a non-natural origin … as a serious potential hypothesis,’ ” Andersen says.

Meeting via Slack and other virtual portals, the researchers analyzed the virus’s genetic makeup, or RNA sequence, for clues about its origin.

It was clear “almost overnight” that the virus wasn’t human-made, Andersen says. Anyone hoping to create a virus would need to work with already known viruses and engineer them to have desired properties.

But the SARS-CoV-2 virus has components that differ from those of previously known viruses, so they had to come from an unknown virus or viruses in nature. “Genetic data irrefutably show that SARS-CoV-2 is not derived from any previously used virus backbone,” Andersen and colleagues write in the study.

“This is not a virus somebody would have conceived of and cobbled together. It has too many distinct features, some of which are counterintuitive,” Garry says. “You wouldn’t do this if you were trying to make a more deadly virus.”

Other scientists agree. “We see absolutely no evidence that the virus has been engineered or purposely released,” says Emma Hodcroft, a molecular epidemiologist at the University of Basel in Switzerland. She was not part of Andersen’s group, but is a member of a team of scientists with Nextstrain.org that is tracking small genetic changes in the coronavirus to learn more about how it is spreading around the world.

That finding debunks a widely disputed analysis, posted at bioRxiv.org before peer review, that claimed to find bits of HIV in the coronavirus, Hodcroft says. Other scientists quickly pointed out flaws in the study and the authors retracted the report, but not before it fueled the notion that the virus was engineered.

Some stretches of the virus’s genetic material are similar to HIV, but that’s something that stems from those viruses sharing a common ancestor during evolution, Hodcroft says. “Essentially their claim was the same as me taking a copy of the Odyssey and saying, ‘Oh, this has the word the in it,’ and then opening another book, seeing the word the in it and saying, ‘Oh my gosh, it’s the same word, there must be parts of the Odyssey in this other book,” she says. “It was a really misleading claim and really bad science.”

Andersen’s group next set out to determine whether the virus could have been accidentally released from a lab. That’s a real possibility because researchers in many places are working with coronaviruses that have potential to infect humans, he says. “Stuff comes out of the lab sometimes, almost always accidentally,” he says.

A couple of unexpected features of the virus caught the researchers’ eyes, Andersen says. In particular, the gene encoding the coronavirus’s spike protein has 12 extra RNA building blocks, or nucleotides, stuck in it.

This spike protein protrudes from the virus’ surface and allows the virus to latch onto and enter human cells. That insertion of RNA building blocks adds four amino acids to the spike protein, and creates a site in the protein for an enzyme called furin to cut. Furin is made in human cells, and cleaves proteins only at spots where a particular combination of amino acids is found, like the one created by the insertion. SARS and other SARS-like viruses don’t have those cutting sites.

Scientists and journalists share a core belief in questioning, observing and verifying to reach the truth. Science News reports on crucial research and discovery across science disciplines. We need your financial support to make it happen – every contribution makes a difference.

Finding the furin cutting site was a surprise: “That was an aha moment and an uh-oh moment,” Garry says. When bird influenza viruses acquire the ability to be cut by furin, the viruses often become more easily transmissible. The insertion also created places where sugar molecules could be fastened to the spike protein, creating a shield to protect the virus from the immune system.

The COVID-19 virus’ spike protein also binds more tightly to a protein on human cells called ACE2 than SARS does (SN: 3/10/20). Tighter binding may allow SARS-CoV-2 to more easily infect cells. Together, those features may account for why COVID-19 is so contagious (SN: 3/13/20).

“It’s very peculiar, these two features,” Andersen says. “How do we explain how this came about? I’ve got to be honest. I was skeptical [that it was natural]. This could have happened in tissue culture” in a lab, where viruses may acquire mutations as they replicate many times in lab dishes. In nature, viruses carrying some of those mutations might be weeded out by natural selection but might persist in lab dishes where even feeble viruses don’t have to fight hard for survival.

But then the researchers compared SARS-CoV-2 with other coronaviruses recently found in nature, including in bats and pangolins. “It looks like SARS-CoV-2 could be a mix of bat and pangolin viruses,” Garry says.

Viruses, especially RNA viruses such as coronaviruses, often swap genes in nature. Finding genes related to the pangolin viruses was especially reassuring because those viruses’ genetic makeup wasn’t known until after SARS-CoV-2’s discovery, making it unlikely anyone was working with them in a lab, he says.

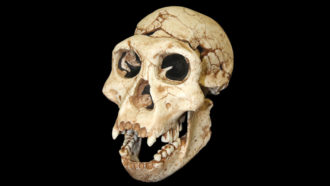

Coronaviruses that infect pangolins gave researchers important clues that the SARS-CoV-2 virus is natural. 2630ben/iStock/Getty Images Plus

In particular, pangolins also have the amino acids that cause the tight binding of the spike protein to ACE2, the team found. “So clearly, this is something that can happen in nature,” Andersen says. “I thought that was very important little clue. It shows there’s no mystery about its tighter binding to the human [protein] because pangolins do it, too.”

The sugar-attachment sites were another clue that the virus is natural, Andersen says. The sugars create a “mucin shield” that protects the virus from an immune system attack. But lab tissue culture dishes don’t have immune systems, making it unlikely that such an adaptation would arise from growing the virus in a lab. “That sort of explained away the tissue-culture hypothesis,” he says.

Similarity of SARS-CoV-2 to bat and pangolin viruses is some of the best evidence that the virus is natural, Hodcroft says. “This was just another animal spillover into humans,” she says. “It’s really the most simple explanation for what we see.” Researchers still aren’t sure exactly which animal was the source.

Andersen says the analysis probably won’t lay conspiracy theories to rest. Still, he thinks the analysis was worth doing. “I was myself skeptical at the beginning and I kept flipping back and forth,” Andersen says, but he’s now convinced. “All the data show it’s natural.”

Questions or comments on this article? E-mail us at feedback@sciencenews.org

Tina Hesman Saey is the senior staff writer and reports on molecular biology. She has a Ph.D. in molecular genetics from Washington University in St. Louis and a master’s degree in science journalism from Boston University.

Science News

Science News was founded in 1921 as an independent, nonprofit source of accurate information on the latest news of science, medicine and technology. Today, our mission remains the same: to empower people to evaluate the news and the world around them. It is published by Society for Science & the Public, a nonprofit 501(c)(3) membership organization dedicated to public engagement in scientific research and education.

Log in

Subscribers, enter your e-mail address to access the Science News archives.

Breaking News Emails

On March 17, when the Navajo Nation saw its first COVID-19 case, the reservation's limited health facilities sprang into action.

"We basically changed our hospital from an acute care hospital and an ambulatory care clinic to one that could take care of respiratory care patients," said Dr. Diana Hu, a pediatrician at one of the reservation hospitals. "And that transition happened over a period of about seven days."

It didn't take long for one case to turn into two, and then 20. As of Monday, the Navajo Nation, which sprawls across three states, had 1,197 positive coronavirus cases. It has a per capita infection rate 10 times higher than that of neighboring Arizona and the third-highest infection rate in the country behind those of New York and New Jersey. Forty-four people have died, more than in 14 other states.

Coronavirus batters hard-hit Navajo Nation

With only 12 health care facilities across 27,000 square miles and a prevalence of chronic health issues like diabetes, the largest and most populous reservation in the U.S. is doing everything it can to cope with an outbreak that is expected to get even worse.

The fear is based on precedent. During the H1N1 flu epidemic in 2009, Native Americans died at four to five times the rate of other Americans.

"We don't know what's going to happen. We don't know if there's lasting immunity. We don't know if you can get re-infected," Hu said.

Hu said that at the Navajo-run hospital in Tuba City, Arizona, where she has practiced for 35 years, there is now a steady supply of personal protective equipment and no shortage of beds, but a 30 percent deficit in critical nursing staff means the hospital has already reached its capacity.

"We have dietitians that are in the screening tent. We have orthopedic surgeons that are doing triage," Hu said.

So far, hospitals in the Navajo Nation's hardest-hit areas have been able to transfer their most critical patients — those needing intubation and potentially weeks of care — to major hospitals in nearby cities like Phoenix and Flagstaff. But doctors worry that if those cities become inundated with their own cases, transfers might not be an option.

This site is protected by recaptcha Privacy Policy | Terms of Service

"I watched the trends very, very early, and quite frankly, I was very concerned. We deal with a tremendous amount of health disparities out here, which leave us with a very vulnerable population," said Dr. Loretta Christensen, chief medical officer for the Navajo Nation at the federal government's Indian Health Service. Christensen said she's expecting a surge of new coronavirus cases in two to three weeks.

The Navajo Nation began educating its citizens earlier than many states about social distancing and hand-washing, but Christensen said part of the problem is that the advice rings hollow for many on the reservation.

"You're telling people, 'Wash your hands for 20 seconds multiple times a day,' and they don't have running water. Or you're saying, 'Go buy groceries for two or three weeks and shelter in place and don't come out,' but people can't afford groceries for two or three weeks. So it's just a setup for frustration and concern by the population here."

When combined with the comorbidities, or pre-existing conditions, that already plague the Navajo Nation — like heart disease, diabetes and obesity — public health experts worry that difficulty accessing basic needs like food and water is going to compound the crisis.

"Our federal government, since treaties were signed in the late 19th and early 20th century, has broken promise after promise after promise," said Allison Barlow, director of the Center for American Indian Health, or CAIH, at Johns Hopkins University's Bloomberg School of Public Health. "And what we're seeing today is the accumulation of those broken promises and where it has left people."

"There has been chronic underfunding of the health systems and infrastructure, from electricity to plumbing to water supplies. All of these things are inflaming the COVID epidemic right now," Barlow said.

To help alleviate the frustrations, CAIH and other public health groups that have long been active on the reservation are stepping in.

CAIH is building hand-washing stations for citizens without running water and delivering care packages of food, water and cleaning supplies to remote homes and the elderly.

The Community Outreach and Patient Empowerment program, or COPE, a nonprofit focused on native health that grew out of Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston a decade ago, has helped turn local motels into respiratory care facilities for the homeless population in Navajo country.

Both CAIH and COPE are supporting the Indian Health Service with contact-tracing, and both organizations, which operate on donations and grants alone, estimate that their monthly costs for health activities on the reservation have doubled during the pandemic.

The U.S. government funds tribal health care, as agreed upon in historic treaties between the U.S. and American Indian tribes, but the Navajo Nation — among other tribal nations — has faced crippling delays in receiving emergency funding.

Download the NBC News app for full coverage and alerts about the coronavirus outbreak

Since COVID-19 began sweeping across Indian country five weeks ago, the Navajo Nation has spent $4 million from its own coffers, President Jonathan Nez told NBC News.

"I'm keeping all these receipts, because after this emergency operation, I'll be giving those receipts to Uncle Sam for a full reimbursement," Nez said. He noted that traditional sources of revenue for the tribal nation, like its casino and coal mine, have been shut down because of the virus.

Nez said that federal funds finally began to trickle into the tribal nation earlier this month and that Indian Health Service facilities received rapid-response tests and additional ventilators, but he said they still need more assistance.

"These dollars that were allocated by Congress and signed into law by the president are monies to help U.S. citizens," he said. "And, you know, it just seems alarming that the first citizens of this country are kind of pushed to the back burner."

On Thursday, the tribal nation made the unprecedented move of putting out a public call for donations, asking for money as well as supplies like N95 masks, hand sanitizer and thermometers for health care workers and the community.

Friday marked the deadline for the 574 tribal nations to submit their requests for funds from an $8 billion sum that was appropriated for American Indian tribes as part of the March coronavirus stimulus package known as the CARES Act. Tribal nations have been told that those funds will be disbursed by Friday.

"We are a sovereign nation, but we're a ward of the federal government, and so we have to wait until decision-makers are able to, I guess, collaborate and agree upon themselves that this is the time to assist Indian Country," Navajo Nation Vice President Myron Lizer said.

For health care providers like Hu in Tuba City, that means hoping for the best and preparing for the worst.

"We're kind of feeling like we're at maybe mile 3.5. We've had the sprint start, and we kind of have to pace ourselves. So what we're doing is we're trying to strategize," she said. "Let's hope that the flattening of the curve occurs so we don't overwhelm anyone in the medical systems, but if we don't, let's plan as if we need to keep this on until September."

Kenzi Abou-Sabe is a reporter with the NBC News Investigative Unit.

Cynthia McFadden is the senior legal and investigative correspondent for NBC News.

Christine Romo is a senior enterprise producer at NBC News.

Читайте также: