Что такое фарминг вирус

Pharming is a form of online fraud involving malicious code and fraudulent websites. Cybercriminals install malicious code on your computer or server. The code automatically directs you to bogus websites without your knowledge or consent.

The goal is to get you to provide personal information, like payment card data or passwords, on the false websites. Cybercriminals could then use your personal information to commit financial fraud and identity theft.

How can you help protect yourself against pharming? Here’s some information and tips that can help.

What is pharming?

Pharming combines the words “phishing” and “farming.” This cybercrime is also known as “phishing without a lure.”

Phishing is an online fraud scheme where a cybercriminal hopes you’ll click on a compromised email link which takes you to a fake site where you then enter your access credentials — such as your username and password. If you do, the fraudster can then access the real site and steal your personal information there.

Pharming, on the other hand, is a two-step process. One, cybercriminals install malicious code on your computer or server. Two, the code sends you to a bogus website, where you may be tricked in providing personal information. Computer pharming doesn’t require that initial click to take you to a fraudulent website. Instead, you’re redirected there automatically. The fraudster has immediate access to any personal information you enter on the site.

How pharming works

Pharming exploits the mechanics of Internet browsing. To understand how pharming works, it’s important to understand how Domain Name System (DNS) servers work.

DNS servers translate domain names into IP addresses. While websites use domain names for their addresses, an IP address denotes their actual location. Your web browser then connects to the server with this IP address.

Once you visit a certain website, a DNS cache forms so you don’t have to visit the server each time you return to the site. Both the DNS cache and the DNS server can be corrupted by pharming. This can result in two types of pharming.

In this case, you may pick up a Trojan or virus via a malicious email or download. The malware then covertly reroutes you to a fake site created and controlled by fraudsters when you type in your intended website address.

In this form of pharming, malicious code sent in an email can change your computer’s local host files. These corrupted host files can then direct your computer to fraudulent sites regardless of the Internet address you type.

Domain Name Systems are computers on the Internet that direct your website request to the right IP address. A rogue, corrupted DNS server, however, can direct network traffic to an alternate, fake IP address.

This pharming scam doesn’t rely on corrupting individual files, but rather occurs at the DNS server level by exploiting a vulnerability. The DNS table is essentially poisoned, so you’re being redirected to fraudulent websites without your knowledge.

If a large DNS server is corrupted, cybercriminals could target and scam an even larger group of victims.

How to protect yourself against pharming

A good place to start is to install and run reputable antivirus and anti-malware security software with browser monitoring to help detect malware threats and protect your devices against emerging threats. But keep in mind not all antivirus and spyware removal software can protect against pharming, so additional anti-pharming measures may be needed.

Here are some anti-pharming safeguards.

If you suspect you’re already a victim of pharming, you can try resetting your computer to reset your DNS entries.

Look for the signs of pharming

Here are two signals of pharming.

- An unsecure connection. If your site address says “http” instead of “https” in the address line, the website may be corrupted.

- A website that doesn’t seem right. If the site you’re on has spelling errors, unfamiliar font or colors, or otherwise just doesn’t seem legitimate, it may not be.

Examples of pharming

A real-world example of pharming was reported by Symantec in 2008 with the first case of a “drive-by” pharming attack on a Mexican bank.

In this case, hackers changed the DNS settings on a customer’s unsecure, home-based broadband router via an email that appeared to be from a legitimate Spanish-language greeting card company.

The malicious code in the email changed the user’s router to redirect their web browser to the attacker’s fake, fraudulent bank site.

Another example of a more sophisticated pharming attack occurred in 2017, when more than 50 financial institutions found themselves to be the recipients of a pharming attack that exploited a Microsoft vulnerability, creating fraudulent websites that mimicked the bank sites targeted.

The victims — online customers in the United States, Europe and Asia-Pacific — were lured to a website with malicious code that then downloaded a Trojan along with five files from a Russian server.

When these customers visited the fake sites from their infected computers, their account login information was sent to the Russian servers. This pharming attacked infected approximately 3,000 PCs in a three-day period.

As these cyberattacks show, pharming could be a major threat for people using e-commerce and online banking websites.

That’s why it’s important to know about pharming and learn what you can do to help protect against it.

How will the COVID-19 pandemic affect California’s agricultural sector—which is important for food supplies locally, nationally, and in many other countries? We talked to Cannon Michael—a sixth-generation farmer and member of the PPIC Water Policy Center Advisory Council—about the pandemic’s potential to disrupt farming.

PPIC: What risks does the virus bring to California’s farm sector?

CANNON MICHAEL: For most farmers, the immediate focus is on our workers—not only keeping them safe from the virus, but also being mindful of the pressures they’re facing at home right now. Most of our workers can’t work from home. Many have kids out of school or partners who’ve lost their jobs.

The big concern going forward is the virus going through our workforce. The disruptions of food supply we’re seeing in stores right now is caused by changes in buying habits and difficulty keeping shelves stocked. But if there’s disruption on farms—if crops don’t get harvested in time or the logistics for getting food to market go down, that would be much scarier. We’re already facing labor uncertainty due to changes to a visa program that allows workers from Mexico and Central America to come here for seasonal farm work. Many of California’s larger farms rely heavily on this temporary labor force. In the early days of the crisis, the H-2A visa program was restricted so that only workers already in the program last year were allowed to come back this year. Rule changes and congestion have made getting across the border harder, too. We’re seeing a slowdown of workers at a time when we may need more. That’s a real concern for the food supply.

There’s a finite pool of people living here to do the hand work required on the state’s farms. There’s a risk that the large companies will do whatever it takes to get those folks if they can’t get seasonal laborers. It could be a threat to smaller farms if larger entities start to pull workers away using incentives that smaller farms can’t match.

The disruption of markets—such as the closure of restaurants and food service operations—is a huge concern for growers. Impacts will vary by region, commodity, and individual company exposure. Western Growers reports that some farmers are heavily embedded in the food service supply chain with crops in the ground now. They have nowhere to put that food, because other growers with retail channels for those commodities are operating at maximum capacity and can’t take any more product into their systems. Other farmers say they may need to scale back acreage. Some crops could be affected by changing international markets or the general financial downturn. There’s the potential for huge swings in marketability and profitability for many farmers.

We’re also not sure if there will be any new requirements for food safety in coming months. There are already good protocols in place for food safety that anyone involved in fresh produce has to comply with, and farmers are accustomed to these high standards. The good news is that food safety experts say there is a low risk of getting the virus from food products or packaging. The advice from the experts is that normal food safety practices will suffice.

PPIC: What steps are being taken to protect farm workers from infection?

CM: We are rapidly approaching the time when most farms will be extremely busy, which means a lot of people on the farm. New state guidance on protecting farmworkers from COVID-19 is being developed. But most farmworkers live in very close conditions and so even with safe practices on the farm, it’s going to be harder to control the risk in their homes and communities under current conditions. If the virus gets into the farmworker population I think we’d see a very fast rise in infection, which would have a dramatic impact on the farm sector and food supply.

On our farm we’re providing regularly updated health information in all the places that people congregate. The California Farm Bureau and industry groups have reacted quickly to make information available in English and Spanish. We’re making sanitation equipment widely available, and presenting guidelines on hand washing and social distancing.

PPIC: What policy changes could help address these risks?

CM: Fixing federal immigration policy is critical. The key point is we need to get food off the farms, and to do that we have to have enough laborers. One hopeful sign is that the federal government recently announced it will relax the new restrictions on the H-2A program. That should help people get here to work.

It’s also critical that rural communities aren’t forgotten in this public health crisis. We need a plan to address the special public health challenges in farm communities.

I don’t want to pound people over the head with this, but the crisis really drives home the importance of agriculture and the value of a stable food supply.

And I’d just like to encourage everyone to reduce the panic buying, which has created big challenges in the supply chain as well as making it harder for more vulnerable people who can’t shop that way. We will produce the food and get it to the markets but we will all be safer if people just buy what they need.

From our Obsession

How to feed everyone, without hurting the planet.

One of the largest farmworker unions in the US says early polling of farm laborers suggests operators of some of the nation’s largest fresh produce farms aren’t taking steps to protect fieldworkers from the spread of Covid-19. That’s worrying news for a food supply chain that experts, so far, have described as robust and resilient in the face of the disease caused by the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2.

The nature of how the coronavirus spreads—from person to person, through droplets from coughs or sneezes, and transferred on surfaces—means that outbreaks have concentrated first in densely-populated urban and suburban zones. But it will reach rural farming areas on a delay (pdf), according to data collected (and visualized over time) by the University of Iowa’s Rural Policy Research Institute.

That means any farmers who have not been proactive about protecting their workers may have already unwittingly invited the virus into the food supply chain.

Farmworker unions represent a fraction of the nearly 888,000 people hired to pick fresh produce in US crops and groves, most of which are in central California, Florida, Washington state, and Texas. Still, insight from fieldworkers can shed light on what’s happening across the fractured landscape of independent farms.

“Unfortunately, I wish I could say more is being done,” says Armando Elenes, the secretary treasurer of United Farm Workers, a California-based farmworkers union with between 8,000 and 10,000 members. The union regularly polls workers through social media to get a sense of what pickers are experiencing on the job. It isn’t scientific, Elenes cautioned, but the results are concerning.

“As of [March 30], 77% of workers are reporting that nothing has really changed,” he says. “That’s really alarming for farmworkers because they feel obligated. If they don’t go to work, they don’t get a paycheck.”

If that polling accurately reflects what’s happening—or not happening—on farms across the US, it could have a global impact. The more than 400 commodities grown in California represent 13% of US agricultural value, totaling some $50 billion in business each year. For a sense of how consolidated agriculture is, consider that just two California farms supply about 85% of US carrots. If the virus were to disrupt production at the largest of the state’s 77,500 farms, it would be felt globally; a 2018 report (pdf) by the state’s department of food and agriculture put its combined agricultural export value at $20.5 billion.

Supply experts feel optimistic about how the food supply chains have reacted to the spread of Covid-19. They are quick to praise the work at the ends of supply chains, where grocery stores have dealt with an intense round of consumer stockpiling.

But they generally agree that the biggest point of weakness is likely at the very beginning of the chain, on the farms. Daniel Stanton is a former executive at Caterpillar who has taught at supply chain management at colleges and authored Supply Chain Management for Dummies. As he thinks about how the food system gets goods from farms to grocery stores, Stanton says his top concern is whether farmers and ranchers are protecting their workers from getting the virus.

The threat is higher for some areas of agriculture than others, says Ananth Iyer, a supply chain and operations management expert at Purdue University’s Krannert School of Management, depending on how much they rely on human labor.

The largest grain and soybean operations in US Midwestern states, France, Russia, Ukraine, Turkey, Australia, China, and India, are mostly automated. Large planting and harvesting tractors can get the job done with minimal human interaction.

“It’s a different ballgame in respect to grapes, tomatoes, and avocados,” Iyer says, noting that harvesting fresh fruits and vegetables often requires the gentler handiwork of human pickers.

A proactive response to the virus would involve changing daily workflows that gather many laborers in the same space, where it’s harder to practice the social distancing encouraged by health experts. Morning meetings for disseminating marching orders would have to be broken into smaller groups. Transporting pickers to harvesting fields and groves—which often involves packing workers into vans for drives that can last more than half-an-hour—would have to be staggered. And daily lunch breaks would have to be spread out for workers to promote social distancing.

The people who oversee agricultural operations have every market-based reason to implement and ensure laborers abide by rules that promote safer working conditions, Iyers says. For those who don’t, a sick and incapacitated workforce could set off a chain reaction of problems that last years.

“If we don’t have the people, supply will decrease,” Iyer says. “If supplies decrease and demand remains the same, prices will go up. At some point, customers shift what they eat, and once they give up on it they go elsewhere.”

Iyer adds that it can take years and lots of marketing money to nudge people back toward buying certain foods with regularity.

“I’m hoping executives at every stage of the supply chain are anticipating these things and putting pieces in place to address them,” he says.

For some, this appears to be the case. Coral Gables, Florida-based Fresh Del Monte Produce Inc. is one of the largest distributors of fresh fruit and vegetables, bringing in close to $4.5 billion in sales in 2019, with a gross profit of $312 million. In a March 24 press release, the company said it has incorporated more hand-washing practices and has also reduced the number of employees working on its farms, packing houses, port operations, and production facilities at any given time.

“Any employees showing signs of illness are immediately segregated from the workforce and monitored before being allowed to return,” the statement said. Even these precautions may not go far enough, as the virus is often spread by people who are asymptomatic.

The threat is not just economic. It’s also very human. It is estimated that half the laborers on US farms are undocumented immigrants, according to the US Department of Agriculture. Collectively, these workers pump billions of dollars in taxes into the US economy each year, but they are not eligible for federal unemployment insurance benefits should they lose their jobs or fall ill. They also are not included in the $2 trillion stimulus package passed by Congress, part of a wide-ranging relief plan for businesses and people affected by the spread of Covid-19.

Asked about the compelling market incentives for growing operations to adopt safer practices, Elenes explains that some believe changes will cut into overall farm efficiency.

“They are putting profits over people,” he says.

The next several of weeks will be telling for the US, as the virus reaches further into farming communities and a true picture of their preparedness is revealed. As the food supply chain waits for that to happen, it will be important for consumers to keep the situation in context, says Yossi Sheffi, a professor of engineering systems at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

“Food is grown all over the United States, it’s not likely that all these farming communities will be hit at once,” Sheffi says. “Some will be hit harder than others.”

The current situation, and the possibility of disruption in the food system, has Sheffi recalling his childhood in Israel, where his family experienced temporary shortages of certain foods. During an egg shortage, for instance, his mother would have him eat seven olives a day because she believed they collectively had as much protein as an egg. Sheffi’s point is clear: For the average consumer, intermittent shortages of specific foods won’t be devastating.

“Even if you say you don’t have avocados for some weeks, you don’t have avocados, it’s not the end of the world,” he says. ”Let’s make sure the doctors and nurses get all the equipment they need. Let’s make sure the agricultural workers get all the equipment they need.”

Farmworkers keep their distance from each other as they work at the Heringer Estates Family Vineyards and Winery in Clarksburg, Calif.

Source: AP Photo

Farmers are being hit by falling commodity prices, labor shortages, and difficulties related to planting, harvesting and transporting crops as the virus that causes the COVID-19 illness tightens its grip around the world.

In Europe, the closure of thousands of restaurants, resorts and hotels as well as a plunge in catered meals at now-shuttered business offices and schools have lowered demand for basic agricultural goods. Countrywide lockdowns have forced many seasonal laborers to stay at home, depriving their families of an income and farms of a much-needed workforce.

In the U.S., fewer Mexican seasonal workers are moving across the border, disrupting farms' plans for spring planting and for bringing in crops ready for harvest, such as lettuce in California, berries in South Carolina and tomatoes in Florida.

Farmers in poorer places are especially vulnerable, including those who work in aquaculture and fisheries. At greatest risk are those in parts of sub-Saharan Africa, where chronic hunger and famine are everyday concerns.

"We risk a looming food crisis, unless measures are taken fast to protect the most vulnerable, keep global food supply chains alive and mitigate the pandemic's impacts across the food system," said the Food and Agriculture Organization, or FAO.

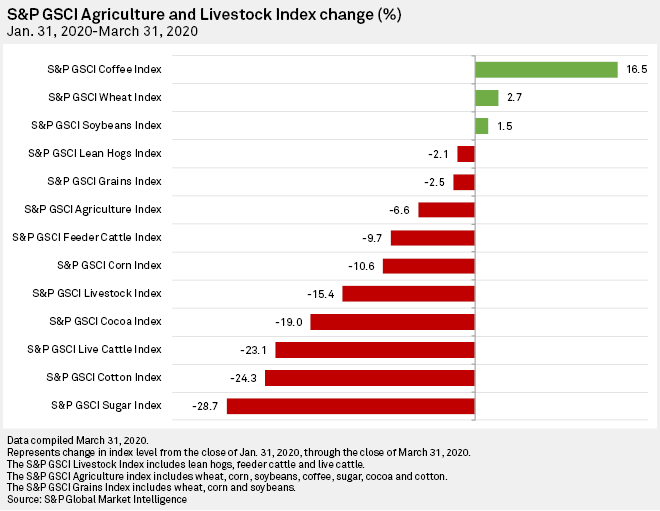

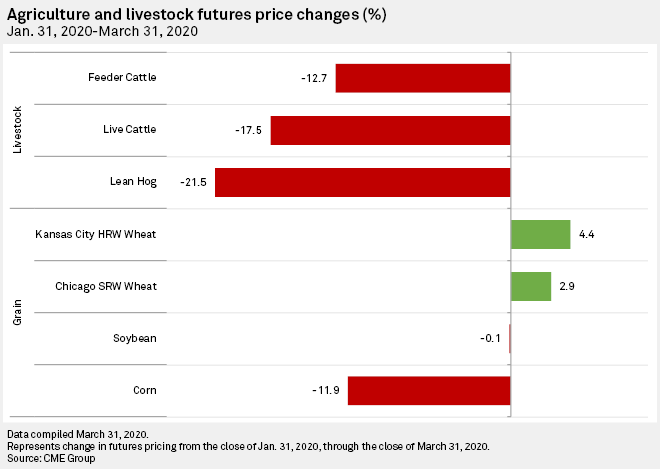

On April 2, the FAO reported that world food prices declined sharply in March, driven mostly by demand-side contractions linked to the pandemic. Between February and March, the FAO sugar price index fell 19.1%, the vegetable price index fell 12%, and the dairy price index fell 3%.

About 20% of U.S. agriculture depends on seasonal workers, most of whom come from Mexico. Based on the number of work visas processed so far, "the shortage is 7%, and any shortage will have a big impact," said John Newton, chief economist at the American Farm Bureau Federation, an i nsurance company and lobbying group that represents the U.S. agriculture industry .

Farms in many western European countries, including Italy, Spain, Germany and the U.K., also depend heavily on seasonal workers. In addition to the 1.1 million permanent workers on European farms, orchards and dairies, there are seasonal workers who do the equivalent work of 700,000 full-time agricultural laborers, including harvesting, pruning and planting. Many travel from eastern European countries such as Bulgaria and Romania to do seasonal work in the 26 countries that make up the Schengen bloc in Europe. Most were unable to travel as of March 17, when the European Union closed all Schengen borders for at least 30 days.

"There is a clear risk that we have endangered food security, especially in fruits and vegetables," said Pekka Pesonen, secretary general of Copa Cogeca, a pair of European organizations that represent 23 million farmers and their family members and 22,000 agricultural cooperatives, respectively. "The border restrictions and reduced movement of people could have a potentially devastating impact on our farming because we don't have a labor force for [the annual spring] planting. If we don't plant, we can't harvest."

Place UK, a closely held company near the English city of Norwich, grows strawberries, cherries, blackberries and rhubarb across 400 acres of land covered in polythene tunnels. It sells frozen produce to some of the U.K.'s biggest supermarket chains, including Tesco PLC and J Sainsbury PLC. Each spring and summer, the company recruits about 650 seasonal workers, mainly from Bulgaria and Romania, but that has become harder in 2020.

"We're OK for people until May 20, but not sure what will happen from mid-May to mid-June. It's a serious problem for everybody," said Tim Place, managing director.

According to Place, Britain's horticultural industry hires up to 70,000 seasonal workers each year, but the coronavirus outbreak has stymied many of those plans. Although Place UK hopes to recruit temporary workers from the U.K.'s hospitality sector, which has largely shut down, it will not be easy. Farm work requires "you to be on your feet all day and it can be monotonous," Place said.

Because of expected restrictions for people as a result of Brexit, by October 2019, Britain had already seen a 45% decline in seasonal agricultural workers compared to usual levels, according to Jonathan Owens, a logistics expert at the University of Salford Business School in the U.K. "Farmers were already finding it difficult to complete the harvest then," Owens said. Currently, the U.K.'s asparagus crop, which has a small window for optimum picking, needs to be brought in. Without more farmhands, some of it may rot in the fields, Owens said.

Other producers are in a bind because they supply food only to schools and restaurants, many of which have closed down. In Europe, 10% to 15% of all food is catered, according to Pesonen. Farms that used to sell high-value cuts of beef to the restaurant business, for example, now are trying to adjust by selling lower-profit minced beef that is in greater demand from supermarket shoppers. The upshot: a decline in profit.

"Across key local and regional markets (i.e. farmers markets, farm to school, food hubs serving other institutions, and restaurants) we expect to see up to a $688.7 million decline in sales leading to a payroll decline of up to $103.3 million, and a total loss to the economy of up to $1.32 billion from March to May 2020," concluded the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition, a U.S. alliance of grassroots agricultural groups. "Without immediate mitigation, we may lose many small, socially disadvantaged, and beginning farms and the important markets they serve."

Smaller businesses in Europe are hurting too. "People have stopped buying flowers," Pesonen said. In the U.K., the Netherlands, Belgium and elsewhere, "they've had to destroy 60% to 70% of flowers because there's no market. Millions of dollars of investment have been lost."

Falling demand has triggered a decline in the prices of many agricultural commodities, including cattle and corn. The U.S. dairy industry saw milk prices rebound in 2019, but those prices have since fallen 15% to 20% in the face of the coronavirus pandemic, Newton said.

Governments are trying to help. The EU said e nsuring food security and an effective food supply chain across the continent was one of its priorities. "We are facing an unprecedented crisis," Agriculture Commissioner Janusz Wojciechowski said during a March 25 video conference with EU agriculture ministers. To support the agri-food industry, the EU adopted temporary measures whereby farmers can now benefit from aid of up to €100,000 per farm and food processing and marketing companies can benefit up to €800,000.

For U.S. farmers, the repercussions of the coronavirus contagion may play out in other ways. Under a "phase 1" trade pact with the U.S., China agreed to purchase an additional $40 billion per year of meat, poultry and other farm products over a two-year period, and as of late February, there were signs that the plan was on track. Will it still be fulfilled?

"We want it to occur but we're facing a global economic slowdown," Newton said. "China is indicating that they're planning to live up to their commitments . It's too early to say whether it will or won't happen."

READ MORE: Sign up for our weekly coronavirus newsletter here , and read our latest coverage on the crisis here .

A member of the Women's Land Army examines an experimental plant at the Potato Virus Research Station (ca. 1940s).

Photo courtesy of Library & Archives, John Innes Centre, Norwich.

Supervisory team: ">Dr Helen Anne Curry (Department of History & Philosophy of Science, University of Cambridge) and Dr Sarah Wilmot (Library & Archives, John Innes Centre)

Applications are invited for an Open-Oxford-Cambridge AHRC DTP-funded Collaborative Doctoral Award at The University of Cambridge, in partnership with the John Innes Centre (JIC).

In 1927, the UK Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries founded the Potato Virus Research Station at Cambridge University. The station became home to what was then an ever-more-urgent area of research in Britain and abroad: the control of plant diseases associated with viruses, which were little understood at the time. Scientists associated with the research station, which later became the Plant Virus Research Unit of the Agricultural Research Council (ARC), then the ARC Virus Research Unit, and still later the Virus Research Department of the John Innes Centre (JIC), remained at the forefront of international plant virus research for the next nine decades. This was true even as the focus of research changed from the urgent matter of keeping disease-free potato stocks for plant breeding and cultivation to understanding the molecular structure of the gene to devising biotechnological applications for plant viruses.

This project offers the opportunity to prepare a pathbreaking account of the development of plant virus research in Britain, drawing especially on the extensive and largely untouched archives related to this research held at the JIC in Norwich. This subject has never been treated in a scholarly account despite many acknowledgments of the critical role of plant virus research in the history of twentieth century biology. The research student will home in on three distinct eras: virus control in crop plants at the Potato Virus Research Station, molecular biological investigations at the Virus Research Unit, and the development of industrial biotechnology at the JIC Virus Research Department. The result will be a novel account of some of the most important changes in biological research in the past 100 years.

As part of the project, the research student will have the opportunity to develop skills related to archive development and public history, for example in assisting the JIC archives in creating catalogues for the relevant collections and taking oral histories of past and present JIC researchers. In collaboration with the JIC outreach team, the student will be invited to develop a public exhibition that will be installed in 2024 to celebrate the centenary of publicly funded plant virus research in Britain.

The research student will be supervised by Dr Helen Anne Curry of the University of Cambridge, who has expertise in the history of modern biology and biotechnology. Dr Sarah Wilmot, Outreach Coordinator and Science Historian at JIC, will offer additional supervision and coordinate the use of the JIC Library and Archives. Based at the Department of History and Philosophy of Science (HPS) at Cambridge while collaborating with the JIC, the research student will move between two world-leading research communities: in the histories of modern science, medicine, and technology at Cambridge HPS, and in plant science, genetics, and microbiology at the JIC in Norwich.

Applicants with masters-level training in the arts, humanities, or social sciences are encouraged to apply, with the fields of history, history of science and medicine, science & technology studies, and sociology particularly desirable. Candidates with experience in plant sciences are also encouraged to make inquiries.

For further details on how to apply for this CDA through the University of Cambridge, please see the advert on the Cambridge jobs site.

Читайте также: