Откуда холера на гаити

Медики бьют тревогу, нужно как можно скорее обеспечить питьевой водой жителей Гаити и предоставить технологии для ее очистки

Медики бьют тревогу, нужно как можно скорее обеспечить питьевой водой жителей Гаити и предоставить технологии для ее очистки

Смертоносный ураган "Мэттью", разбушевавшийся в конце сентября, потихоньку ослабевает. Страны, по которым он пронесся, приходят в себя, но опасность все еще остается. Теперь государства Карибского бассейна сталкиваются с новой проблемой - холерой. Число смертей от этой острой инфекции стремительно растет, а одна из самых бедных стран мира - Гаити - может снова пережить ужас 2010 года, когда началась эпидемия холеры, унесшая жизни несколько тысяч человек.

Гаити также со смелостью можно назвать одной из самых несчастных стран, поскольку она постоянно страдает от стихийных бедствий. После урагана "Мэттью" островное государство снова оказалось в беде.

Стихия буквально смыла целые города, мосты и дороги разрушены, что затрудняет доставку медикаментов, питьевой воды и продовольствия. Больше всего разрушений на юго-западе Гаити.

В городе Жереми 80% зданий были повреждены или разрушены, а в городе Ле-Ке практически 90%. Также сильно пострадал городок Порт-Салют, там ураган разрушил около половины зданий.

Точное число жертв урагана "Мэттью" на Гаити неизвестно. В ООН говорят, что официально подтверждена смерть 372 человек, местные власти уже заявили о более тысячи жертв, и эта цифра будет расти по мере того, как спасатели будут добираться в труднодоступные районы. В ООН констатируют, что в Гаити в помощи нуждаются 1,4 миллиона человек.

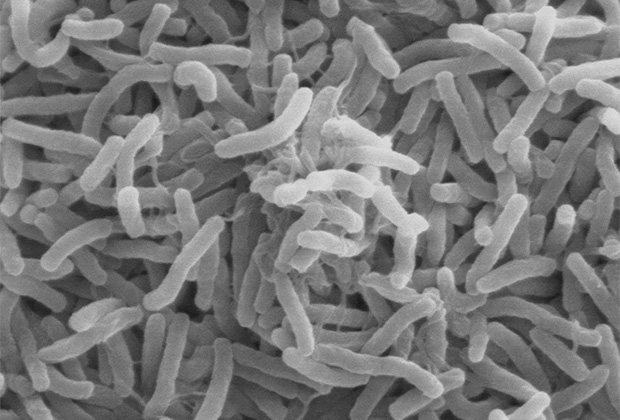

Разрушения, принесенные Мэттью, подрывают многолетние старания по борьбе с холерой. Холера является острой диарейной инфекцией, вызываемой при попадании в организм пищевых продуктов или воды, зараженных бактерией Vibrio cholerae. В ВОЗ отмечают, что инфекция чрезвычайно заразна, она поражает как детей, так и взрослых и может приводить к смерти за несколько часов. Симптомы болезни появляются от 2 часов до 5 дней.

Новости по теме

Новости по теме

Медики бьют тревогу, нужно как можно скорее обеспечить питьевой водой жителей Гаити и предоставить технологии для очистки воды. Сейчас известно о 13 погибших от холеры, еще более сотни обратились за помощью с подобными симптомами. В Службе гражданской защиты Гаити сказали, что только в одном Жереми известно о 40 случаях холеры.

В городе Жереми уже развернули центр по лечению холеры.

Больница в Ле-Ке переполнена пострадавшими в ходе смертоносного урагана.

В большинстве городов и поселков по-прежнему нет электроэнергии, запасы воды и пищи кончаются, а доставить их практически невозможно из-за размытых дорог. Безвыходное положение толкает жителей нападать на гуманитарные конвои, известно о нескольких таких случаях.

Новости по теме

Новости по теме

ООН запросила у доноров 120 миллионов долларов для оказания помощи Гаити. Сейчас из Центрального фонда реагирования на чрезвычайные ситуации уже выделили 5 млн долларов, чтобы помочь стране. Также направлена группа специалистов для оценки масштабов ущерба и размера помощи, в которой нуждаются жители.

Как безобидный микроб веками убивал миллионы людей по всему миру

Фото: Margaret Bourke-White / The LIFE Picture Collection / Getty Images

Сами виноваты

Холера — молниеносное заболевание, способное убить человека за сутки. Его возбудитель — бактерия Vibrio cholera — один из рекордсменов по числу устроенных пандемий. Хотя сейчас холера считается болезнью бедных стран с плохо развитой инфраструктурой (вспышки происходят в Гаити, Ираке, Йемене и африканских странах), в прошлом она свирепствовала в развитой Европе, истребляя вообще всех. В XIX веке произошло сразу шесть пандемий, которые унесли жизни десятков миллионов людей.

Принято считать, что холера возникла из-за колонизация британцами Южной Азии, а также индустриальной революции, которая проложила микробу дорогу в Европу и Северную Америку. В какой-то степени именно холера стала причиной появления водопровода и канализации, ведь самым эффективным средством против болезни оказалась чистая вода. Появилась новая парадигма: инфекции возникают там, где царит антисанитария и отсутствует гигиена. Правда, в современном мире чистота уже не всегда залог здоровья, и новые патогены, вроде золотистого стафилококка, могут распространяться даже в стерильных больничных боксах.

Холерный вибрион изначально был безобидным микробом и обитал в мангровом лесу Сундарбана (Индия и Бангладеш), где участвовал в симбиотических взаимоотношениях с веслоногими рачками. Долгое время на нога человека почти не ступала эти территории, однако во второй половине XVIII века сюда вторглись английские колонисты. Через сто лет люди расселились почти по всему Сундарбану и жили по колено в солоноватой воде, кишащей зараженными веслоногими. Продолжительные и тесные контакты позволили вибрионам постепенно адаптироваться к организму человека, но они сразу не стали убийцами.

Шустрая зараза

Ключевым приобретением Vibrio cholera стал токсин, который заставляет кишечник действовать наоборот: высасывать воду с электролитами из тканей самого организма и вызывать диарею и обезвоживание.

В Европе XIX века холеру считали унизительным заболеванием, лишающим человека достоинства и уравнивающим его с нищими и жителями трущоб. Возбудитель холеры загрязнял улицы, питьевую воду, оставался на руках больных и здоровых и — распространялся. Вспышка заболевания шла волной, поражая новые города и буквально стремясь к Европе.

Холера разносилась через транспортные пути и свирепствовала везде, где царила антисанитария, где люди жили бок о бок с фекальными отходами. Роковую роль сыграла и перенаселенность, в частности — разрастание трущоб, где вибрионы без труда проникали в грунтовые воды. Лишь жилищные реформы позволили снизить смертность от холеры и других инфекций в западных странах, однако в бедных регионах планеты до сих пор в ужасных условиях живут сотни миллионов человек.

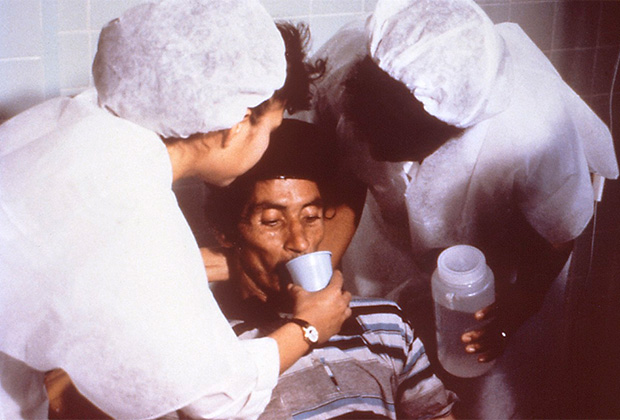

Оральная регидратация у больного холерой

Холерная истерия

В Испании жители Мадрида решили, что эпидемию холеры вызвали монахи, отравившие колодцы по политическим причинам, и начали громить церкви и молельные дома. Похожая ситуация возникла в Сан-Франциско, где толпа учинила расправу над представителями ордена францисканцев. Жертвами погромов и кровопролития стали иммигранты, хотя вина во многом лежала на домовладельцах, которые превратили иммигрантские кварталы в плотно заселенные трущобы. Поначалу во всем винили ирландцев, которые, как считалось, принесли холеру в США. Затем общество переключилось на мусульман-паломников, совершающих хадж. В конце XIX века объектом ненависти стали иммигранты из Восточной Европы, в том числе венгры и российские евреи.

Слив нечистот в озеро в Гаити

В 2010 году в Гаити произошла крупнейшая в XXI веке вспышка холеры, которая унесла жизни 4,5 тысячи человек. Санитарная обстановка на Гаити оставляла желать лучшего, источником распространения инфекции стала заполненная нечистотами река. В то же время гаитянцы уверены, что холера попала на остров из-за вооруженных сил ООН, которые намеренно занесли ее из Непала. Результаты исследования генома возбудителя показали, что холера действительно была занесена из Непала, однако с большой долей вероятностью переносчик был латентным носителем, который не подозревал, что в нем притаилась холерная бомба. Но этого было достаточно, чтобы на Гаити начались столкновения и массовые беспорядки.

Хотя причину появления холеры на острове в целом определили верно, вспышка достигла масштабов эпидемии из-за других факторов, включая вырубку лесов и гражданскую войну, а также антисанитарию и проблемы местной инфраструктуры в Гаити.

В 2006 году эпидемиологи предсказали, что в течение жизни двух следующих поколений возникнет холероподобная пандемия, способная вызвать спад экономики и убить до 200 миллионов людей. Однако тогда ни один из патогенов-микроорганизмов (ни ВИЧ, ни возбудители гриппа) не дотягивала до уровня холеры. Одним из ключевых показателей способности патогена вызвать эпидемию или пандемию является базовый показатель репродукции (БПР или R0), который равен среднему числу лиц, заражаемых носителем инфекции. Для SARS-CoV-2 БПР оценивается от 2 до 6,47 — почти те же значения, что и для холеры. К счастью, пока COVID-19 не может сравниться со смертоносным кишечным расстройством ни по масштабам, ни по числу смертей.

Cholera patients are treated at the Cholera Treatment Center in the Carrefour area of Port-au-Prince, Haiti, in December 2014. The Caribbean country's cholera outbreak started in 2010. Hector Retamal/AFP/Getty Images hide caption

Cholera patients are treated at the Cholera Treatment Center in the Carrefour area of Port-au-Prince, Haiti, in December 2014. The Caribbean country's cholera outbreak started in 2010.

Hector Retamal/AFP/Getty Images

In the fall of 2010, months after a devastating earthquake struck Haiti, a new disaster began: a cholera outbreak that killed thousands of people and continues to sicken people across the country.

Experts determined that the source of the disease was a U.N. peacekeeping camp. And now, nearly six years later, the United Nations has admitted it played some role in the deadly outbreak.

At a briefing Thursday, U.N. spokesman Farhan Haq said that over the course of the past year, "the U.N. has become convinced that it needs to do much more regarding its own involvement in the initial outbreak and the suffering of those affected by cholera."

He said the U.N. would announce new actions to address the issue within the next two months.

"Our legal position on this issue has not changed," Haq said, adding that the U.N. was not describing any of its actions as "reparations."

The U.N.'s acknowledgement was first reported by the New York Times, which notes that the statement from Haq "stopped short of saying that the United Nations specifically caused the epidemic." The newspaper adds:

"Nor does it indicate a change in the organization's legal position that it is absolutely immune from legal actions. . But it represents a significant shift after more than five years of high-level denial of any involvement or responsibility of the United Nations in the outbreak, which has killed at least 10,000 people and sickened hundreds of thousands."

Cholera, as our Goats and Soda blog has explained, is an infectious disease that causes severe, watery diarrhea. It spreads through contaminated water. The illness causes dehydration and can lead to death, sometimes in just a few hours, if left untreated.

The beginning of the epidemic in Haiti was swift and catastrophic. Here's how Richard Knox described the outbreak for NPR in 2013:

"Suddenly, the first cases appeared in the central highlands near a camp for United Nations peacekeeping forces. .

"The disease struck with explosive force. Within two days of the first cases, a hospital 60 miles away was admitting a new cholera patient every 3 1/2 minutes.

" 'Part of the reason we think the outbreak grew so quickly was the Haitian population had no immunity to cholera,' says Daniele Lantagne, an environmental engineer at Tufts University. 'Something like when the Europeans brought smallpox to the Americas, and it burned through the native populations.' "

Before 2010, cholera had been unknown in Haiti for at least a century. And the impoverished, earthquake-devastated country was already struggling with water and sanitation.

A panel of experts appointed by the U.N. found that the strain of cholera that popped up in Haiti was "a perfect match" for a strain found in Nepal. Nepalese peacekeepers were staying at the U.N. camp, and poor sanitation sent sewage from the camp into local waterways.

In 2013, activists sued the U.N. over the cholera outbreak. Earlier this year, NPR's Jason Beaubien offered an update on that case:

"A three-judge federal appeals court panel held a hearing March 1 on whether the U.N. should be held accountable for Haiti's devastating epidemic.

"A federal district judge last year dismissed the class-action suit, ruling that international treaties immunize the U.N. from lawsuits. The plaintiffs appealed the lower court's dismissal, resulting in this month's hearing. The United States is defending the U.N., since the agency is headquartered in New York.

"The lawsuit was brought by the Boston-based Institute for Justice and Democracy in Haiti and a sister group in Haiti on behalf of 5,000 cholera victims. They want the U.N. to end cholera by installing a national water and sanitation system; pay reparations to cholera victims and their families; and publicly apologize for bringing cholera to Haiti.

"The plaintiffs contend the U.N. forfeited its legal immunity when it failed to launch an internal process to adjudicate the plaintiffs' claims, as they say its own commitments require.

" 'The U.N.'s conditional immunity does not authorize impunity,' plaintiffs' attorney Beatrice Lindstrom told the three-judge appeals panel."

As the Times noted, the U.N. did not walk back its claim of immunity in its acknowledgement of some responsibility in the outbreak.

As Jason reported, U.N. officials are concerned that if the U.N. is held responsible for the cholera outbreak, it will be vulnerable to lawsuits around the world over actions of its peacekeeping forces. Some of the U.N.'s own special rapporteurs have sharply criticized that stance and say U.N. efforts to address the crisis are "clearly insufficient."

Again, the cholera crisis that began in 2010 continues. The disease is now endemic in the country; thousands of people are sickened every year.

Senior Lecturer, International Development Department, University of Birmingham

Professor of Law, Conflict and Global Development, University of Reading

Nicolas Lemay-Hébert receives funding from the AHRC, the ESRC, and the Jacob Blaustein Institute.

Rosa Freedman receives funding from the AHRC, the British Academy, the ESRC, and the Jacob Blaustein Institute.

University of Birmingham provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation UK.

University of Reading provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

The Conversation UK receives funding from these organisations

- Messenger

The United Nations is once again denying proper justice to victims of cholera in Haiti. Perhaps the UN hopes it can make good by apologising, which it did at the end of 2016, and accepting that it was at least partly involved in the initial outbreak of the disease. But this isn’t enough. And while it promises to prevent future outbreaks and offer remedies to victims, its efforts are proving inadequate.

The UN has to put its money where its mouth is – to listen to the individuals it harmed and to provide them with the remedies that they so desperately need.

Since 2004, the UN has maintained a peacekeeping mission (MINUSTAH) to help stabilise and rebuild the country. After a devastating earthquake in 2010, more peacekeepers arrived; the UN did not screen them for cholera, which had never been present in Haiti. Some peacekeeping camps had only inadequate toilet facilities, which were used by Nepalese peacekeepers carrying cholera; as a result, raw cholera-contaminated sewage found its way into Haiti’s main river, the Artibonite, upon which vast numbers of Haitians depend. The disease quickly spread around many parts of the country, and it’s thought to have killed around 10,000 people.

It wasn’t just the initial outbreak that devastated families and communities. The disease was neither contained nor eradicated, and the disease is still present in Haiti today. After years of pressure through advocacy campaigns and a class action lawsuit, the UN has pledged to provide remedies through what it calls a “victim-centred approach”.

But what’s fast becoming apparent is that any consultations with victims will only take place after the UN determines what those remedies will look like. And that means they won’t take into account victims’ own ideas of what they need.

Missing the point

The UN’s plan for Haiti includes both a commitment to consult with victims and a preference for collective reparations, but it’s succeeding on neither front. Building health centres and schools or providing “other collective remedies” may be worthwhile, but it won’t help put victims back in the position they were in before cholera killed and sickened almost one tenth of Haiti’s population. What many of the victims really need is money.

In March 2017, we travelled to Haiti to observe the work of the public interest lawyers who represent the cholera victims. Those victims we met are not seeking vast sums; they are asking for small cash transfers to allow them to buy back land or cattle they had to sell to pay for travel to a hospital, or to pay back the money they had to borrow to bury their dead relatives. They want enough to pay for basic things – getting their children to school, for instance – that they could afford before coping with the cholera outbreak saddled them with debt.

A Doctors Without Borders facility in Carrefour, Haiti. EPA/Bahare Khodabande

These people told us that they don’t trust either the UN or the state to finish the health centres and schools they’ve promised to build. Even if they are completed, they will hardly solve everyone’s problems. They won’t help families who lost a parent to provide for their children, or to buy back possessions they sold in desperation six years ago.

As one man told us, the projects “will mean that [we] victims see nothing other than big cars driving down the road blowing more dust into our faces”.

Falling short

Providing remedies in the form of cash payments is not unusual, even for the UN. There’s even precedent for giving them out after epidemics: the UN Development Programme recently offered cash transfers to people in Ebola-struck areas of West Africa, not as compensation, but as a means to mitigate the devastating effect of losing breadwinners or taking on debt to pay for treatment.

The UN went to these lengths even though it didn’t cause the Ebola outbreak, so surely it can bring itself to compensate the victims of an epidemic which its peacekeepers were involved in causing. But the UN Development Programme isn’t offering cash payments to Haiti’s cholera victims. Why? Because the money and political will aren’t there.

Whereas the Ebola cash transfers came out of the UN’s budget, money for the cholera effort is meant to come in the form of voluntary donations from UN member states, who have so far collectively contributed only a tiny percentage of the target amount. This is yet another slap in the face for the victims: the UN played a role in causing the outbreak, and its budget can certainly spare the money required.

Is this behemoth of an organisation really so worried about the consequences of giving a couple of hundred dollars each to some of the poorest people in the world? This epidemic is a terrible stain on the reputation of the UN and its peacekeeping missions, and it will only be removed if a proper resolution package is created and implemented.

And whatever form that package takes, it must be built around victims’ actual needs and concerns, not the UN’s own idea of what they might be.

-

June 26, 2017

Even as the United Nations expresses growing alarm over a cholera outbreak in war-ravaged Yemen, the organization is increasingly worried about the fallout from a stubborn cholera scourge in Haiti that was caused by its own peacekeepers more than six years ago.

A $400 million voluntary trust fund for Haiti to battle cholera was created last year by Ban Ki-moon, then the secretary general, when he apologized for the United Nations’ role after having repeatedly denied any responsibility. But the fund, meant in part to compensate cholera victims, garnered only a few million dollars and is now nearly empty.

Entreaties by Mr. Ban’s successor, António Guterres, for charitable contributions have gone unanswered. Moreover, a proposal announced on June 14 by Mr. Guterres’s office to repurpose $40.5 million in leftover money from the soon-to-be disbanded peacekeeping mission in Haiti for use in the cholera fight has faced strong resistance from other countries.

Without an immediate infusion of funds, warned his deputy secretary general, Amina J. Mohammed, “the intensified cholera response and control efforts cannot be sustained through 2017 and 2018.”

Last week, Mr. Guterres appointed a new special representative for the Haiti cholera crisis — the third one so far — to devise new fund-raising solutions.

And on Friday, United Nations officials were served with a reminder that their effort to shield the organization from Haiti cholera lawsuits by asserting diplomatic immunity might not necessarily work. In papers filed in Federal District Court in Brooklyn, the lead lawyer for Haitian victims challenged a request for dismissal of their case by the Justice Department, which acted on behalf of the United Nations.

The arguments by the lead lawyer, James F. Haggerty, differed from those in a separate lawsuit filed by the Institute for Justice and Democracy in Haiti, an advocacy group, which argued that the United Nations had failed to give victims a way to settle their grievances. A federal appeals court dismissed that suit last August at the Justice Department’s request.

The Justice Department has until July 7 to respond to Mr. Haggerty’s filing, which argues that the United Nations established as far back as the 1990s that it was legally liable for damages caused by negligence from peacekeeping operations.

Acceptance of that liability, Mr. Haggerty said, was the same as waiving immunity under the treaty the United Nations has invoked as protection, known as the Convention on the Privileges and Immunities of the United Nations.

That treaty, he said, “should not be a shield to hide behind because the United Nations (or the U.S. government) doesn’t like the price tag that comes with the U.N.’s indisputable gross negligence in this case.”

United Nations officials indicated on Monday that they expected Mr. Haggerty’s lawsuit to be dismissed as well. “Our legal position remains the same,” said Stéphane Dujarric, a spokesman for Mr. Guterres. “Our focus is on combating cholera and assisting impacted communities.”

Roughly 10,000 Haitians have died and nearly a million have been sickened since cholera was introduced into Haiti in 2010 by infected United Nations peacekeepers from Nepal. Studies showed the cholera bacteria came from poor sanitation by the peacekeepers.

The United Nations never acknowledged it was at fault, and even when Mr. Ban apologized last December for its failure, he worded the apology to avoid any mention of who had brought the cholera to Haiti, the Western Hemisphere’s poorest country.

Mr. Ban’s solution was to create the $400 million voluntary trust fund — in effect, a charitable gesture to show good will and demonstrate what he called a “moral responsibility” to make things right in Haiti.

Haitian anger over the cholera issue was clear last week when the United Nations Security Council visited Haiti before the planned October dismantlement of the peacekeeping mission, which has been deployed there for 13 years. Hundreds of protesters demonstrated outside the mission’s base.

Critics of the United Nations have argued that its response to Haiti’s cholera crisis remains deeply flawed, with no guarantee of ever redressing victims as long as donations are voluntary.

Article

When Hurricane Matthew struck on October 4, 2016, it left 1.4 million people in southern Haiti in need of urgent humanitarian assistance; it destroyed homes and health care facilities, flooded water sources with runoff, ruined crops, killed livestock, and displaced hundreds of thousands of people. Looming as the next act in the disaster is a resurgence in endemic cholera.

Cholera had not been recorded in Haiti until it was introduced in 2010. The introduction of Vibrio cholerae into a population that had never been exposed to cholera and that had extremely limited access to safe water and sanitation had a predictable effect: an explosive cholera epidemic that has killed at least 10,000 people and caused nearly 800,000 reported cases throughout the country. 1

Now in its seventh year, the epidemic has taken an immeasurable toll on individuals, communities, and the health system in Haiti, and the resources for controlling it have been too limited. In 2015, Haiti reported more cases of cholera per population than any other country. In 2016, there were 29,000 cases of cholera in the first 9 months of the year — already a disaster before the hurricane hit. And as is so often the case, the poor have suffered the most. New approaches are needed to address the ongoing problem and mitigate suffering from cholera in Haiti. The hurricane’s aftermath adds urgency to this problem.

On October 13 and 14, 2016, the minister of health and population of Haiti, Daphnee Benoit, convened an expert panel at the U.S. National Institutes of Health to consult on the control of cholera in Haiti with specific reference to the use of vaccines in the aftermath of Hurricane Matthew. Two weeks after Hurricane Matthew, the number of cholera cases had grown, and many were concerned about the impact on human life. The consultation resulted in the following consensus.

The response to Hurricane Matthew must first and foremost address the victims’ need for humanitarian relief, through provision of food, shelter, and clean water to those who lack these lifesaving essentials. Rallying emergency clean-water activities to combat the known risk of cholera in the immediate phase is an important strategy. We should assume, at least initially, that there has been further contamination of freshwater sources in Haiti’s southern peninsula. Ensuring that people have access to and use effectively chlorinated water, with safe water storage at home (or in shelters), is a critical lifesaving objective.

There is a simultaneous need to ensure that cholera treatment centers and oral rehydration posts are functional. After the hurricane, many of these facilities will have to be rebuilt; resupplied with rehydration fluids, antibiotics, and zinc for children; and supported with staff to perform effective case finding in the community and rapid treatment of the sick. These strategies have not changed since the beginning of the cholera epidemic in 2010, although in recent years resources to implement them have dwindled.

When the cholera epidemic began in Haiti, and for some years afterward, there was a lack of consensus on the role that oral cholera vaccine (OCV) could play in the response. One clear issue, however, was that the supply of vaccine was very limited, and there was limited experience in using OCVs in response to outbreaks. Furthermore, the fact that the most affordable vaccine had not yet met prequalification requirements of the World Health Organization (WHO) meant that the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and other United Nations agencies could not purchase it.

Since that time, a number of developments have enhanced our ability to control the epidemic in Haiti. Two safe, effective OCVs are now available at an affordable cost ($1.70 to $1.85 per dose), are prequalified by the WHO, and are available in increasing quantities. The products are essentially the same vaccine, made by different manufacturers. Shanchol (Shantha Biotechnics, India) was prequalified in 2011. In 2013, a 2-million-dose OCV stockpile was established as a public good to manage the vaccine. Euvichol (Eubiologics, South Korea) was prequalified by the WHO in 2015, and the manufacturer recently announced that it could produce 25 million single-dose vials per year that remain stable at 37°C for 30 days, avoiding waste and enabling delivery to the most remote areas without requiring a stringent cold chain. Other OCVs are available (VaxChora, PaxVax, United States; Dukoral, Valneva, Sweden) but at this time are not considered practical for major public health use in resource-poor settings.

Finally, a series of studies with OCVs in Haiti have demonstrated the efficacy of the Shanchol vaccine in both urban and rural settings, the feasibility of achieving high coverage rates, and the low cost of delivering this vaccine to the population. In one of the poorest urban slums of Haiti, not a single case of culture-confirmed cholera occurred between September 2013 and August 2016 in persons who had received a combined intervention ensuring household chlorination and cholera vaccination. 2-4 This research complements other recent OCV studies from Guinea and South Sudan.

This information fundamentally changes the way health authorities should now consider the use of OCV in controlling cholera. Mass vaccination in Haiti would save lives, and modeling suggests that such an intervention, coupled with targeted, effective water, sanitation, and hygiene interventions, could substantially control, if not eliminate, the disease within a few years of the program’s introduction, at an affordable cost. This medium-term plan will have to be undertaken in concert with a long-term effort to realize the human right of access to clean water, a goal that will require a substantial budget and years, if not decades, to accomplish. Control of cholera was a problem in Haiti for the 6 years before Hurricane Matthew — not only because there were insufficient resources, but also owing to the enormity of the challenge of redressing the population’s severely constrained access to clean water and sanitation.

One million doses of OCV were requested by the Haitian Ministry of Public Health and Population and authorized as part of the emergency response to Hurricane Matthew. 5 Two shipments of 500,000 doses arrived in Haiti on October 24 and 25, 2016, and the vaccines have been deployed by the Ministry of Health and its partners for urgent use. We of the Special Consulting Group to the Minister of Health and Population of Haiti commend the mass-vaccination approach in the hurricane-affected areas of the south of Haiti as one part of a comprehensive emergency response. In light of recent data on vaccine efficacy, the feasibility of vaccinating in outbreak settings, and the increased availability of safe, effective, and low-cost vaccines, we urge, in addition to an emergency response to cholera in the hurricane-affected communities, that intense and reinvigorated support be provided to the government’s National Plan for the Elimination of Cholera in Haiti, including a nationwide two-dose oral cholera vaccination campaign.

Over the past six decades, several public health programs in Haiti (e.g., those focused on HIV care and treatment and control of neglected tropical diseases) have provided models for the world. The increased availability of OCVs and their rollout in a national program could provide an opportunity for the government of Haiti and the international community to demonstrate another successful strategy: comprehensive national OCV coverage combined with targeted water, sanitation, and hygiene interventions could eliminate the transmission of cholera in Haiti over the next 3 to 5 years at an affordable cost (some estimates suggest approximately $66 million). This goal is surely one to aspire to, given the human cost of maintaining the status quo.

Eliminating cholera transmission in Haiti with a combined, integrated approach at the population level would be a major achievement for the government and people of Haiti. It would also have broad implications for the control of cholera in other affected populations around the world. The time for ambitious action on cholera control and elimination in Haiti is now.

Читайте также: